21. Februar 1944

I can’t fall asleep. Midnight has long since passed and I toss and turn restlessly on my bunk. The nervous tension of the last two days and the anger about the battalion commander are still rumbling inside me. A thousand thoughts flit through my brain, chasing sleep away. And I need it so badly after the exertions of the last few days! Hour after hour passes. 3 o’clock in the morning - 4 o’clock in the morning.

Today is the 21st of Feb. 44.

The phone rattles. I lift the receiver to my ear and hear the excited voice of Russenmüller: “Alarm! The Russian has broken into our trench again in the same place. Get company ready immediately. Report to me!” I can still hear him calling the infantry gun company as he hangs up. He probably wants to request a barrage.

The tiredness is blown away. As I’m sleeping almost dressed, I am quickly ready and rush to the battalion command post. The battalion leader receives me straight away with the situation report: “Schrödter, the Russian is in our trench again, in the same section as the day before yesterday. Toss him out!” And then he picks up the phone again as I leave the command post. I climb down into the crew bunker. The men had already been alerted by the battalion and were almost ready, but were in no particular hurry. Some are still buckling up, one is still eating, another is doing some major business. So much composure almost gets me up in arms again. There are only a few of them, but they are delaying the action. What’s more, it’s stupid. Because the brighter it gets, the more difficult it is to approach the enemy. The later we arrive, the more firmly the Russian has barricaded himself in the trench and reinforced his position. We have to pay for the consequences of such slowness with our blood. But the Landsers don’t think that far ahead. I urge them to hurry and give the order to take a box of hand grenades with them. Then the first groups set off.

The first men of the platoon, whom the Russian has now thrown out of the trench for the second time, come towards me at the large strawstack in our second line at the top of the slope. First and foremost the sergeant “leading” the platoon. I order him to join the counterattack. His men reluctantly turn back, but the sergeant raises objections. I immediately realise that this wimpy bunch is completely demoralised. The sergeant is a coward. That’s why the platoon has failed, because their leader is no good. So I prefer to let them go back and climb down the slope alone with my men.

The second counterattack begins. My watch shows 6 o’clock. It is already light. The sky is clear. The air is cold.[1] Visibility is excellent. It is the most hideous attack position imaginable. The Bolsheviks are sitting in the bunkers and in the cover of the trench, while we have to attack over a completely open, snow-covered area that offers no concealment other than the deep snow. In addition, the slope towards the enemy is still slightly inclined, so that he can clearly see even the last man on the smooth, white snow surface.

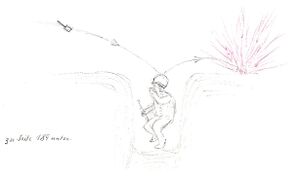

Here we go! Brookh-brookh-brukh! Mortar! So we are recognised. No wonder, with our colourful green camouflage clothing we stand out perfectly against the white blanket of snow. We were lying flat in the snow from the very first impact. Now there is a small pause. They correct their shooting values. We have to be out of here before the next salvo comes. As I’m in the lead, I turn round and want to shout an order to the men. Sure enough, some of them are already running back! I thunder at them to throw themselves down immediately and come crawling back. These are the guys who cause panic in a split second of shock and pull everything back with them. Roomm-woomm - a new series of impacts. Between the impacts, I shout: “Go for the trench, the mortars can’t reach us there!” And then: “Work ahead in squads! Jump up, at the double!” I jump up and run forwards. A few spirited Landsers immediately join in. A good example is better than an explanation. We work our way forwards, jumping. Two hundred metres to go. The mortar fire has stopped. There are only a few shots from the trench. I don’t even recognise it yet. As working my way through the deep snow is very tiring, I just stand up and walk forwards. It remains quiet. The men now also follow me, walking upright. We approach the trench, weapons at the ready.

“Careful, Herr Leutnant, the Russians have a machine gun in the trench!” The call comes diagonally from the front. That’s when I recognise them. Diagonally to the left, fifty metres away, three German Landsers are lying behind a small, flat snowdrift. Three Landser with a light machine gun (lMG). They left the trench to the rear during the surprise attack by the Russians tonight, but immediately took up position again behind this small snow bank and kept the Soviets at bay from here. So they have been lying here in the snow for three hours, fifty metres in front of the occupied trench, the muzzle of their machine gun pointed at the breach and firing at everything that moves in the trench.

I reach them in a few jumps and throw myself into the snow next to them. From here I can see the occupied trench quite clearly. I also recognise the Russian heavy machine gun. It’s right where I came upon the trench. There is a wall of dead men around the machine gun. I count twelve bodies. That was the work of the three brave men! This machine gun was the most powerful weapon the Russians had at their disposal at the moment. If they could bring it into action, I would have a damn hard time. That’s why the Ivans kept trying to get it into position at the risk of their lives. But as soon as a Red Army soldier tried to get to the machine gun, the three of them threw their sheaves in between. It was a fierce battle. Three men paralyse a twenty-fold superior force because they have courage!

My plan is all ready. First we have to take the machine gun. A few brief orders: “1st platoon attack the first bunker on the right! MG Möller shields against the second bunker on the right! Company squad to me, we take the machine gun! Ready - attack!” I crawl with my squad in a short arc sideways towards the machine gun. The three men with the lMG cover me with fire. Rattling bursts of fire splash between dead and living Russians at their MG/08[2]. Gunfire whips towards us. We return fire, alternately crawling and firing. The Reds let go of the machine gun and retreat into the bunker, from where they put up a fierce defence. One jump - I’m at the Russian machine gun. The first piece of booty. The Ivans have now lost their strongest and most dangerous weapon. A badly wounded Ivan tries to crawl back to the Russian positions. I let him do so. He’s barely making any headway due to his weakness and won’t make it anyway.

I now crawl with my men between the earth-brown corpses towards the first bunker. My 1st platoon is already about to attack it head-on, and now that I’m already in the trench I can also attack it from the side. The trench is snowed over, but because of the packed snow it looks like a narrow, elongated gully. We now have the bunker sandwiched between us, as we are almost in a semi-circle around it. Next to me is my loyal messenger, diagonally in front of me two men with an lMG, behind me a few others and the medic. Pressed flat into the snow, our eyes wide open and focussed on the bunker, our weapons ready to fire, we stalk closer and closer.

The Reds hardly have any room to move. They are crowded into the bunker and the small trench next to it, which is kept free of snow for the sentry. As soon as an Ivan raises his head over the edge of the trench, a few shots whip across from us. The Russians defend themselves and hurl hand grenades at us from cover. They can’t shoot any more, because before they can bring their rifles to bear, our bullets are pelting around their ears.

Then the machine gun crew, lying diagonally in front of me on the right, calls to me. I look over. Gunner 2[3] raises his arm. It is blood red and has a strange shape. Bones shot to pieces. The first wounded man. I send him backwards with a wave of my hand and he crawls back. The medic is right behind me. I turn round and see him already. He lifts his nose over a snow bank and peers over the cover like a rabbit.

The shot came from the second bunker over there. It’s also full of Ivans giving fire support to their oppressed comrades. So I shout a warning: “Watch out for the second bunker on the right!” At the same time, I urge them to hurry: “Go for the first bunker - hooraaay!” We jump towards the bunker as one. The Russians respond with a series of hand grenades, which they hurl at us. They explode in the deep blanket of snow with a muffled, choked sound. Another one of my men tumbles wounded into the snow.

The volley has forced us back to the ground. At least we are now within thirty metres. Penetration distance.

Before I can get ready for the final phase, breaking into the trench, my messenger next to me pulls off another hand grenade and throws it over. It flies in an arc towards the trench and is about to fall into the sentry stand. At the same moment, however, an Ivan suddenly lifts his head to take a quick look over the edge of the trench. The hand grenade hits him right on the steel helmet, ricochets and bounces in a short arc onto the rear edge of the trench, where it thunders to pieces. Ivan was gone in a flash. But the situation was of such original comicality that we guffawed about it later.

My messenger is unstoppable. He pulls off another hand grenade, jumps up and throws it over to Ivan as he runs. I call him back. He is able and jumps into the trench on his own.

“Get ready for penetration!” Old hands know what they have to do now: Get the hand grenade ready, throw it at the same time on command and at the moment of detonation, “Jump up - at the double!”, run the last twenty to thirty metres towards the trench or enemy position, respectively, firing from all weapons. (The method can change, however, depending on the situation.) I raise my sub-machine gun to once more fire at the bunker. There it fails. It has got into the snow as I’m crawling through the deep snow and has packed up.

It’s always the same old story with our weapons. They’re no match for the Russian winter. This sub-machine gun in particular is no good. It goes off too easily in summer and fails in winter when it’s very cold. The Russian sub-machine gun fires in all weathers! It’s the same with our MG 42, an excellent weapon with a high rate of fire and a correspondingly devastating effect - if it fires! But in freezing temperatures it often doesn’t!

While this thought flashes through my mind and I’m about to throw my submachine gun away in anger, two hands are suddenly raised over in the trench. They surrender! We cease fire, I call the Russians, and then they come out. 2 - 4 - 6 - 8 men. Lying on my front, I raise my arm in joy and shout: “Hurray, we’ve won!” The foremost Red Army man comes towards me. He bends down to me, holds out both hands and says: “Spasiba, pan, spasiba!”[4] He is happy to be alive. Now they also want to go straight to the back, away from the front, and ask me repeatedly: “Nasad, pan?”[5] But I order the medic to take them to the pit behind the downed Tiger tank first and wait there until we have cleared out the other bunkers. He can tend to the wounded in the meantime.

Now on to the second bunker! We crawl towards the shelter. To get a better view of it, one of my men rises and stands upright on the hill of the bunker we’ve just captured. Before I can call out to him, a shot cracks and the soldier collapses silently. What recklessness! How can you stand up there in full height as a target when the enemy is lying in wait sixty metres away, fighting for his life! It’s a shame, because this man, too, was one of the best and most decent soldiers in my company. And they’re getting rarer and rarer anyway.

The medic is already at my side. “Herr Leutnant, give me cover, I’ll get him back!” But I don’t want to split up into individual actions, especially as the man is probably dead. So I say: “No, we all have to go forward, then he’ll come to lie behind us anyway. Then you can take care of him!”

Third Wound

I cheer the men on again: “Forward, go for the second bunker!” We push ourselves closer through the snow. We have to press ourselves flat into the snow, because the Ivan shoots at anything that moves. Another wounded man! We have to proceed faster. It’s best to go in one go, fire from every buttonhole and charge! I estimate the distance. It’s not far now. So: “Up, on the double!” I jump forwards in a few quick leaps. Suddenly I feel a sharp pain in my right foot, twist my ankle and sink into the snow. I even think I heard a crack. But there was no gunshot, was there? The foot hurts. I try to stand up, but sink back down again. Foot broken or wounded? I don’t know. It doesn’t matter now. I crawl on all fours towards the bunker. A man falls on the right, badly hit. You can tell that by the way he falls and stays down. You get a good look at it. My foot hurts like hell, but the fight takes up all my senses and thoughts. I only realise subconsciously that I’m always rolling from side to side in pain as I direct the fight. Now I can’t crawl any further because of the pain and stay lying down. We’ve now got so close to the bunker that we can storm it. I order: “Hand grenades ready for penetration!” But we’ve run out of grenades! What a mess! That’s all I need! But luckily, an idea comes to me in a flash. I fall back on a ruse. At the first bunker, we had always accompanied our step-by-step advance with shouts of hurrah, and the Russians had immediately responded with a volley of hand grenades. Let’s try a slightly different approach here. Their supplies must be exhausted at some point, and then we’ll have an easy game. At my command, we all shout “Hurray!” but remain calmly on the ground. The Russians promptly respond with a series of throws. They are thick, oversized hand grenades. Every time we shout now, a cascade of hand grenades flies towards us from the dugout, but always fizzles out ineffectively in the snow. The Soviets no longer dare to raise their heads above cover because they are held down by our rifle fire. They throw their grenades at random in our direction without hitting anyone.

Then we approach the bunker. The first Landser is standing close to it when another hand grenade flies towards him. But the German, standing upright, just turns his upper body to the side until the hand grenade has exploded and then goes for the bunker. We fire a few more bursts at the dugout, the Ivans throw a few more hand grenades, but then their resistance is broken. Three Ivans come out with their hands up. Of course it’s not all of them. “Skolko ishcho tam?”[6], I smatter. They reply that there are still some downstairs who don’t dare come out. I order an Ivan to call them out. We would do them no harm. The Russian turns to the bunker and shouts: “Sovietski camerati, iditye suda. Niemietski soldati nie strelyayout!”[7] After some hesitation, the last three Ivans come crawling out.

I also send them to the hole behind the wrecked tank. This pit was probably meant to be a shelter. Fourteen prisoners have gathered there in the meantime. I dispatch a Landser to take the prisoners up to the battalion. While this group slowly climbs up the slope, I turn my attention to the next bunker.

There are still three bunkers to go. My foot no longer hurts so much. I crawl through the snow on all fours like a dog. My MPi is hopelessly iced up. I now want to attack the third and fourth bunkers at the same time. We open the storm with a cheer. Our rifle bullets hit the cover and the wood of the shelter. Russian hand grenades explode with a muffled bang. If the Reds dare to raise their heads, our bullets are pelting their ears. Since they can no longer see anything, their resistance is aimless and weak. We just go for the bunkers, and when the Ivans throw hand grenades, the Landser just turn to the side to avoid getting splinters in their stomachs. But another one of my men gets wounded in the end. Then this bunker crew also has to surrender. Again, six Russians come out with their hands up.

Nothing is moving in the fourth bunker. Are they trying to deceive us? Then Grenadier Schlodder pipes up: “Herr Leutnant, I’ll take this one alone!” He crawls from the side of the bunker up to the ceiling, pulls out a hand grenade and drops it into the bunker chimney. Then he jumps to the entrance. Inside, the hand grenade explodes with a muffled bang, and at the same moment the grenadier pushes open the bunker door and jumps in. The bunker is empty. The Ivans had fled unnoticed.

I say a few words of appreciation to Schlodder. He’s the type of brash Berliner. A real bully, but exactly the right man for such undertakings. “Herr Leutnant, you think I’m a non-commissioned officer? No, no, here, I’m an ordinary Landser!” With these words in Berlin slang, he pulls his winter camouflage jacket off his shoulder and shows me his simple shoulder strap. It’s probably meant to be a hint, but I decide to submit him for an award.

The fifth bunker is also empty. Schlodder didn’t want to repeat his bravura performance here. That’s better. You shouldn’t tempt fate. Besides, it’s a shame about the bunker ovens, which will of course break in the process and which we still need.

The counterattack is over. Still on all fours, I crawl back to the tiger wreck, let myself slide into the pit and now sit in front of the prisoners. My men also gather here. The Ivans squat in front of me in their thick, brown winter coats and look at me expectantly. Only one of them asks me again, a little uncertainly: “Nasad, Pan?” When I confirm: “Da, da, chas nasad!”[8], a wave of relief goes through the bunch. They perk up and the first ones start to climb out of the pit. But I call them back. I want to hear a few things from them first.

They are Strafnikis, members of a disciplinary battalion. They attacked here the day before yesterday. There were 120 of them and they lost 40 men. This morning they had to repeat the attack with the remaining 80 men. This attack also cost them almost 20 dead and 21 prisoners. And now they are sitting here and are glad to be alive. But they’re not entirely comfortable up here. I can feel them being pulled “backwards”.

A Russian is sitting on the edge of the pit, completely apathetic. His lower leg has been shattered by a bullet and is covered in blood. He is thirsty and asks me for water. But I have nothing to drink. Now I recognise him. It’s the same one who tried to crawl back earlier. He gave it up as hopeless and came back. Now he sits there, still and slumped. A few minutes have passed when the seriously wounded man suddenly starts to moan loudly. His cramped hand begins to describe rapid circles in front of his face, as if in an epileptic fit. As he does so, he emits rising and falling inarticulate sounds ... ouahouehouehouahouahouaaahhoooo ... Delirium. The voice becomes increasingly dull. Then the upper body slowly sinks backwards and falls back lifelessly. His comrades watch this death affected and shaken. We could not help him any more.

I send the last six prisoners back with the medic and two men. There are still some seriously wounded among the prisoners. With the man who has just died, I have taken 21 prisoners.

I now have the captured bunkers reoccupied. I have handed the report of the successfully completed counterattack to the medic: Enemy losses: 20 dead, 21 prisoners. Loot: 1 sMG, 25 rifles. Own losses: 2 dead, 4 wounded.[9]

The two counterattacks cost me 4 dead and 8 wounded. Despite the success, the price paid is high.

At last it is quiet again. I lay down on the straw bed of a bunker to rest my foot. It doesn’t hurt so much any more. Maybe it’s just a sprain. I get up and step carefully. I can walk. I take a few steps. No great pain. I climb out again, observe the enemy area, have the loot weapons collected and then lie down on the straw again. The foot is not all right after all.

It’s midday. But that doesn’t mean anything. We don’t eat until the evening. As I lie on the straw, a thousand thoughts run through my head.

There is no major military action in our section here. It’s a typical trench war, a fierce small-scale war. A battle against infiltrated patrols, penetrated assault troops, a helpless fight against invisible snipers. There were penetrations and counterattacks and everything that the Wehrmacht report calls “reconnaissance and assault troop activity”. The losses, seen individually, are not high. Today a wounded man, tomorrow nothing, the day after tomorrow a dead man. But in the course of time, these losses added up to considerable numbers. We hardly get any replacements.

The Russian once pulled off one of his daring exploits. One stormy night, unnoticed by our sentries, he positioned an infantry gun thirty metres from our trench. Soviet infantry then attacked at dawn. This gun radioed into our trench at close range in such a way that the Landsers immediately fled. The raid was a complete success for the Ivan.

But there is something I noticed repeatedly: That the Russians suddenly hesitate after the first success. It was the same again this time. They had occupied three hundred metres of our trench and then they waited until we fired them out again. Why didn’t they push through? The Russian is a lone fighter of enviable toughness, endurance and skill. But he has no initiative and cannot make independent decisions. He hasn’t learnt that. And the lower and middle command lacks tactical training and experience.

Something else is remarkable. The Russians often attack in the same place again and again despite failure and high losses. I learnt the reason later: it lies in the command structure. A Soviet commander who receives a combat mission is personally responsible for its execution and success. That is why he attacks again and again despite repeated failures. Human casualties are irrelevant. The almost inexhaustible reservoir of men, the military and psychological training and the mentality of the Russian make such an approach possible. The lack of tactical skill is replaced by mass deployment.

A Landser who stood guard on the first night of the Strafniki penetration recounts that the Russians came running silently in a long line in the heaviest snow, with their arms hooked under each other. He only noticed them when they had almost reached the trench.

It is evening now. Darkness has fallen over the positions. The catering sledges have arrived and stop a hundred metres from my bunker. As I try to walk over to the sledges, I suddenly feel a sharp pain in my foot. I stand rooted to the spot and then drag myself back to the shelter. I stay here until the food delivery is finished. Then I have the two dead comrades placed on the first sledge, while the second is loaded with the weapons. Now I have to climb up myself, because I have to see the doctor. Supported by two men, I shuffle to the sledge and push myself onto the seat. Then the horses pull up. They pull up the slope, fall into a trot at the top of the plain and stop a short time later in front of the battalion’s medical bunker. By now it had become completely dark. The doctor comes out and goes to the dead while I slide down into the dugout. I use the time until the doctor returns to call the battalion leader and give him details of the counterattack. I learn that only 19 prisoners have arrived at the battalion. One of the wounded died of his serious injuries on the way there. So the results of my second counterattack are as follows: Enemy losses: 22 dead and 19 prisoners. Own losses: 2 dead and 4 wounded.

The doctor has come back in. He has been with the battalion since 1941 and is a good friend of Max Müller. I describe the course of the injury to him while I carefully and with some difficulty take off the felt boot. It’s difficult because the foot hurts and is swollen: The doctor feels the swelling around the ankle and slightly above it. “Yes,” he says, “it seems to be a sprain. Just go to the train for three days to rest. But to be on the safe side, have yourself examined again at the military hospital.” I painstakingly put my felt boot back on, say goodbye to the doctor and let myself be led out.

The catering sledge is already waiting outside. I get on and sit next to the driver. The horses pull up and with a quiet hiss, the sledge glides out into the winter night. The horses’ hooves clatter on the ground and the sledge rushes quietly through the snow. I turn round.

Behind me on the sledge lie the two dead comrades, silent and stiff. Their pale faces stand out as bright spots against the dark canvas. Poor comrades! You there above all, you wouldn’t need to be lying here if you hadn’t been so criminally reckless. What shall I write to your mother now? But actually it is foolish to scold you. All our lives are in God’s hands. He has probably seen fit to recall you now, and then all the caution would have been of no use to you. You were a dutiful soldier and a good chap.

I’m in the sergeant major’s quarters. It’s a clean house that he shares with the supply and the kitchen corporals. We decide that tomorrow I’ll go with a HF1 that has to go into town anyway. They’ll drop me off at the military hospital. Then I go to bed, into a proper, white-covered bed. I carefully position my foot and am asleep straight away.

|

Editorial 1938 1939 1940 1941 1942 1943 1944 1945 1946 1947 1948 1949 Epilog Anhang |

|

January February March April May June July August September October November December Eine Art Bilanz Gedankensplitter und Betrachtungen Personen Orte Abkürzungen Stichwort-Index Organigramme Literatur Galerie:Fotos,Karten,Dokumente |

|

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. Erfahrungen i.d.Gefangenschaft Bemerkungen z.russ.Mentalität Träume i.d.Gefangenschaft Personen-Index Namen,Anschriften Personal I.R.477 1940–44 Übersichtskarte (Orte,Wege) Orts-Index Vormarsch-Weg Codenamen der Operationen im Sommer 1942 Mil.Rangordnung 257.Inf.Div. MG-Komp.eines Inf.Batl. Kgf.-Lagerorganisation Kriegstagebücher Allgemeines Zu einzelnen Zeitabschnitten Linkliste Rotkreuzkarte Originalmanuskript Briefe von Kompanie-Angehörigen |

- ↑ -8°C (KTB 6th A. NARA T-312 Roll 1493 Frame 000314)

- ↑ probably a Russian PM 1910 similar to the German MG 08

- ↑ The men assigned to a machine gun had specific tasks, which were designated by numbers. Gunner 1 was the gun pointer who fired the machine gun, gunner 2 was the loader who monitored the function of the ammunition belt; gunners 3-5 were the ammo gunners who took away the empty ammunition boxes and fetched new ones. A gun leader (in peacetime a corporal) supervised the operation.

- ↑ {спасибо, пан, спасибо! (Ukrainian) Thank you, sir, thank you!

- ↑ назад, пан? To the rear, sir?

- ↑ сколько ищо (actually еще) там? How many more are there?

- ↑ Советские камеради, идите сюда, немецкие солдаты не стреляют! Soviet comrades, come here, the German soldiers aren’t shooting!

- ↑ да, да, час (сразу) назад! Yes, yes, back in an hour (surely he meant immediately)!

- ↑ 9,0 9,1 Radio message LVII.Pz.Korps to A.O.K.6, 20.49 (KTB AOK 6, NARA T-312 Roll 1492 Frame 001247): “257.Inf.Div. attack south of Nedaiwoda repulsed.”