1946/November/6/en: Unterschied zwischen den Versionen

| (4 dazwischenliegende Versionen desselben Benutzers werden nicht angezeigt) | |||

| Zeile 2: | Zeile 2: | ||

{{Geoinfo | {{Geoinfo | ||

| − | | {{Geoo|Magazin 19 | + | | {{Geoo|Magazin 19 }} position still unknown |

{{Geoo|Meadow area near the slaughterhouse}} {{Geok|https://www.google.de/maps/place/Ulitsa+Kashena,+21,+Smolensk,+Smolenskaya+oblast',+Russland,+214012/@54.7964561,32.0243589,17.08z/data{{gleich}}!4m5!3m4!1s0x46cef805277408df:0xb4157eb56636c777!8m2!3d54.7966111!4d32.0258767}} | {{Geoo|Meadow area near the slaughterhouse}} {{Geok|https://www.google.de/maps/place/Ulitsa+Kashena,+21,+Smolensk,+Smolenskaya+oblast',+Russland,+214012/@54.7964561,32.0243589,17.08z/data{{gleich}}!4m5!3m4!1s0x46cef805277408df:0xb4157eb56636c777!8m2!3d54.7966111!4d32.0258767}} | ||

{{Geoo|Buildings (of the ''Kalinin'' factory)}} {{Geok| KartenURL }} | {{Geoo|Buildings (of the ''Kalinin'' factory)}} {{Geok| KartenURL }} | ||

{{Geoo|Flax Combine}} {{Geok| KartenURL }} | {{Geoo|Flax Combine}} {{Geok| KartenURL }} | ||

| − | {{Geoo|Tileyard | + | {{Geoo|Tileyard }} position still unknown |

{{Geoo| see also [[Smolensk_-_Смоленск|Localisation attempts]] and overview map}} {{Geok|https://umap.openstreetmap.fr/de/map/tagebuchfragmente-orte_266585#12/54.7910/32.0452}} | {{Geoo| see also [[Smolensk_-_Смоленск|Localisation attempts]] and overview map}} {{Geok|https://umap.openstreetmap.fr/de/map/tagebuchfragmente-orte_266585#12/54.7910/32.0452}} | ||

}} | }} | ||

| Zeile 34: | Zeile 34: | ||

In consistent implementation of socialist egalitarianism, women's equality is radically carried out in the Soviet Union (except in the Muslim states). Women do the same hard work as men. But the brigadiers of the women's brigades are mostly men. | In consistent implementation of socialist egalitarianism, women's equality is radically carried out in the Soviet Union (except in the Muslim states). Women do the same hard work as men. But the brigadiers of the women's brigades are mostly men. | ||

| − | '''Magazine 19'''. Cereals are stored in this warehouse. Large stacks of sacks full of potatoes, millet, flour and much else. More rarely, a few sacks of sugar or the like. Our work consisted of unloading the | + | '''Magazine 19'''. Cereals are stored in this warehouse. Large stacks of sacks full of potatoes, millet, flour and much else. More rarely, a few sacks of sugar or the like. Our work consisted of unloading the lorries that brought these goods here from the goods yard and loading other lorries that then took the stuff out again to the individual state-run shops in the city. There wasn’t too much to do. The Russian guards would sometimes slip away, and the Russian nachalnik wasn’t always present either. When we had the opportunity, of course, we put aside some of the rations for ourselves. Every experienced plenny is prepared for such occasions. The bags must always be tight and without holes. It is also useful to have a small bag with you at all times. At present, I always carry a tablespoon with a broken handle on this command. It is easy to store and you can use it to take a spoonful from an open flour sack and put it in your mouth, for example, as you pass by. If you had to do it by hand, you would soon have smeared your hand and mouth and would be betrayed. The fact that the flour sack is open is because it “accidentally” fell down during unloading and burst open. There are other methods, but you must not do it often, because the nachalnik is not stupid. |

In another case at another command, we agreed with the supervisor beforehand: We wouldn’t steal anything (called “zappzerapp” in German-Russian gibberish), and in return he would give us something voluntarily at the end. But not all nachalniks were so philanthropic, and there was often a beating if you were caught in “zappzerapp”. There was a lot of stealing everywhere, by Russians and Germans. It was like an epidemic. One comrade even told me that German prisoners of war were lined up with machine pistols in front of a food magazine because the Russians were stealing too much. | In another case at another command, we agreed with the supervisor beforehand: We wouldn’t steal anything (called “zappzerapp” in German-Russian gibberish), and in return he would give us something voluntarily at the end. But not all nachalniks were so philanthropic, and there was often a beating if you were caught in “zappzerapp”. There was a lot of stealing everywhere, by Russians and Germans. It was like an epidemic. One comrade even told me that German prisoners of war were lined up with machine pistols in front of a food magazine because the Russians were stealing too much. | ||

| Zeile 40: | Zeile 40: | ||

Once we unloaded a goods wagon on a siding of the passenger station. Among the goods was a sack of sultanas. While one of us carried the heavy sack, I went sideways to help support the load. As I did so, I poked my finger into an existing hole to fish out a few sultanas. But the sultanas were a bit frozen and hard, so I broke my fingernails. It was hardly worth it for the few sultanas I managed to grab. Besides, this was a risky venture, because when loading such treasures, as with sugar, there are always a lot of watchdogs (who, by the way, are all hoping to get something for themselves). | Once we unloaded a goods wagon on a siding of the passenger station. Among the goods was a sack of sultanas. While one of us carried the heavy sack, I went sideways to help support the load. As I did so, I poked my finger into an existing hole to fish out a few sultanas. But the sultanas were a bit frozen and hard, so I broke my fingernails. It was hardly worth it for the few sultanas I managed to grab. Besides, this was a risky venture, because when loading such treasures, as with sugar, there are always a lot of watchdogs (who, by the way, are all hoping to get something for themselves). | ||

| − | We stowed millet sacks in the large warehouse. From a sack that had opened, we filled our bags in unguarded moments. I had filled my haversack and went as inconspicuously as possible in front of the gate to put it in our | + | We stowed millet sacks in the large warehouse. From a sack that had opened, we filled our bags in unguarded moments. I had filled my haversack and went as inconspicuously as possible in front of the gate to put it in our lorry standing there. Next to the lorry stood our Mongolian guard. I wink at him and stow my bag in a corner. The Mongolian smiles. When we board the lorry to go home after finishing our work, my bag is gone. The Mongol is still smiling, the scoundrel! |

Benno (von Knobelsdorff) had a different method. He simply let the loose millet trickle into his felt boot, namely the right one. At the end of work, the guard suddenly had us line up and sit down. We had to take off our boots and turn them inside out. Benno took off the (empty) left one. The Ivan wants to see the other one too. Benno puts the left one back on and wants to stand up, but the Russian makes him sit down again. Benno sits down and takes off the left one again. The Ivan didn’t realise. So Benno moved into camp with a somewhat swollen right foot. | Benno (von Knobelsdorff) had a different method. He simply let the loose millet trickle into his felt boot, namely the right one. At the end of work, the guard suddenly had us line up and sit down. We had to take off our boots and turn them inside out. Benno took off the (empty) left one. The Ivan wants to see the other one too. Benno puts the left one back on and wants to stand up, but the Russian makes him sit down again. Benno sits down and takes off the left one again. The Ivan didn’t realise. So Benno moved into camp with a somewhat swollen right foot. | ||

| Zeile 48: | Zeile 48: | ||

Behind the warehouse lies a long end of telephone wire. You can always use something like that, and I roll it up. Then I notice that it's too long and Hans Sölheim, who is next to me, says, “Why don’t you tear off a piece?” I do. In the evening in the camp he says to me: “You committed sabotage today,” and when I look at him uncomprehendingly he continues: “The wire was a telephone line. I had pulled it down before!” | Behind the warehouse lies a long end of telephone wire. You can always use something like that, and I roll it up. Then I notice that it's too long and Hans Sölheim, who is next to me, says, “Why don’t you tear off a piece?” I do. In the evening in the camp he says to me: “You committed sabotage today,” and when I look at him uncomprehendingly he continues: “The wire was a telephone line. I had pulled it down before!” | ||

| − | [[Datei:Smolensk_08_1943_clip_m_Anm.jpg|thumb|<span class="TgbZ"></span>''Some locations of the events according to investigations by the ed.: Clubhouse (camp) - 3-storey factory buildings - cemetery - factory "Kalinin" - track between meadows - slaughterhouse'']] | + | [[Datei:Smolensk_08_1943_clip_m_Anm.jpg|thumb|<span class="TgbZ"></span>''Some locations of the events according to investigations by the ed.: Clubhouse (camp) - 3-storey factory buildings - cemetery - factory "Kalinin" - track between meadows - slaughterhouse (aerial image Aug 43)'']] |

We '''unload peat trains at the western edge of town'''. The goods trains stop here and we simply throw the peat pieces down to the left and right onto the open meadowland. All with our hands, of course. Working with us is a brigade of convicted women and girls. When we complain that we have been imprisoned here for 2 years, they just laugh. 2 years is not a long time at all. After 5 years it would be hard, but 2 years? Nitchevo! | We '''unload peat trains at the western edge of town'''. The goods trains stop here and we simply throw the peat pieces down to the left and right onto the open meadowland. All with our hands, of course. Working with us is a brigade of convicted women and girls. When we complain that we have been imprisoned here for 2 years, they just laugh. 2 years is not a long time at all. After 5 years it would be hard, but 2 years? Nitchevo! | ||

| Zeile 59: | Zeile 59: | ||

I have stolen a few boards and climb back across the attic of the neighbouring house into the stairwell there. Here, starting on the 3rd floor, I knock on every flat door and offer my boards at the minimum price, as a special offer. But nobody wants them. They must get too many such offers. Finally, a woman on the first floor takes pity on me and gives me 4 potatoes for them. | I have stolen a few boards and climb back across the attic of the neighbouring house into the stairwell there. Here, starting on the 3rd floor, I knock on every flat door and offer my boards at the minimum price, as a special offer. But nobody wants them. They must get too many such offers. Finally, a woman on the first floor takes pity on me and gives me 4 potatoes for them. | ||

| − | A few days later I try again with a 2 m long log of 15 cm diameter. This time, however, I run across the courtyard to the next block of houses, always taking cover. But here too I am turned away everywhere. I simply have to leave the log in the hallway.<ref>The paragraphs "Photomaton" and "Easter/Cemetery Visits" that follow here in the original text were saved under the appropriate dates [[ | + | A few days later I try again with a 2 m long log of 15 cm diameter. This time, however, I run across the courtyard to the next block of houses, always taking cover. But here too I am turned away everywhere. I simply have to leave the log in the hallway.<ref>The paragraphs "Photomaton" and "Easter/Cemetery Visits" that follow here in the original text were saved under the appropriate dates [[1947/Dezember/8/en|8 Dec 46]], [[1946/November/2/en|2 Nov 46]] and [[1947/November/1/en|1 Nov 47]], respectively.</ref> |

| − | Hans had discovered a tobacco shop not far from the photo shop ''(see [[ | + | Hans had discovered a tobacco shop not far from the photo shop ''(see [[1947/Dezember/8|below]])'', only 100 m further down the same street. They had very cheap cigarettes and cheap tobacco. He kept this secret to himself and did a good business in the camp with a small mark-up. Then, when he fell ill, he let me in on the secret and described the location of the shop to me. Now I fetched the goods from there, and always a rucksack full at once. Once it took a little longer until I had stowed the numerous packages in the backpack and settled up with the woman. In the meantime, a queue of 6-7 people had formed. But they didn’t say a word and waited patiently until I was done, although they had certainly recognised me as a prisoner of war. |

In the camp, Hans had a Landser who sold the cigarettes for him, for a 50% share. I wanted to earn everything on my own and sell them myself. And while Hans lay on his bunk and rested, I raced around the whole camp to sell my cigarettes. Hans had sold his entire stock, but I hadn't sold a single pack. I'm just not a businessman. Then I made an even bigger mistake. A clever comrade had been watching Hans' cigarette seller. He came on to me and I, in my harmlessness, told him about the shop and one day even took him with me after he had hypocritically explained to me that he was not interested in doing business at all. Since then, this crook is snatching everything away from us by buying in bulk and has spoiled the whole business for us. Hans has never forgiven me for my stupidity. Since then, our friendship has cooled down noticeably. | In the camp, Hans had a Landser who sold the cigarettes for him, for a 50% share. I wanted to earn everything on my own and sell them myself. And while Hans lay on his bunk and rested, I raced around the whole camp to sell my cigarettes. Hans had sold his entire stock, but I hadn't sold a single pack. I'm just not a businessman. Then I made an even bigger mistake. A clever comrade had been watching Hans' cigarette seller. He came on to me and I, in my harmlessness, told him about the shop and one day even took him with me after he had hypocritically explained to me that he was not interested in doing business at all. Since then, this crook is snatching everything away from us by buying in bulk and has spoiled the whole business for us. Hans has never forgiven me for my stupidity. Since then, our friendship has cooled down noticeably. | ||

Aktuelle Version vom 13. Juni 2022, 13:59 Uhr

| GEO INFO | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magazin 19 | position still unknown | |||

| Meadow area near the slaughterhouse | ||||

| Buildings (of the Kalinin factory) | ||||

| Flax Combine | ||||

| Tileyard | position still unknown | |||

| see also Localisation attempts and overview map | ||||

6-8 November. The red October Revolution was celebrated in a big way, as usual. For us it only meant increased guarding.

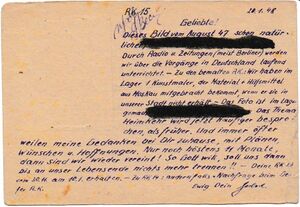

Red Cross cards may now only contain 25 words. Of course, the text will be censored. Information about whereabouts, state of health (if poor), weight and anything negative is deleted (see picture). Disagreeable mail is simply thrown away. This work is also done by the Antifa comrades. Mail is only allowed from Germany and Austria. Mail from other countries is not handed over. The Antifa comrades cannot read foreign languages. I have written 11 times. Of these, 9 cards arrived at home. Delivery time up to half a year.

Bad workers are assembled in a special brigade. This brigade is given a norm that it must fulfil, otherwise the working hours are simply extended. This is forced labour. Extending working hours, shortening breaks, working outside at -40°C, using distrophic workers and countless other violations of the Geneva and Hague Conventions are the order of the day.

We have a larger group of Hungarians in the camp. They are sly fellows, lazy and cunning. When it's their turn to peel potatoes with us, they don’t show up at first, until we finally fetch them after half an hour. And then they start peeling, cutting away so much potato with six short cuts that only a small cube remains. Our scolding doesn’t faze them. They finish their share as quickly as we do, but it results in at least one less bucket of potatoes. These wogs, however, don’t mind. They get on well with the population outside and are also more cunning at stealing than we are, so they always have plenty of extra rations. I think the congeniality between Hungarians and Russians is greater and therefore facilitates their contacts.

The atmosphere in the camp is unpleasant. There is the blind hatred of the “German” camp leadership against us officers. This also applies to some Landser. When I once reprimanded one of them in the washroom for splashing me, he grumbled, “You have nothing to say anymore!” On his way out, he meets a Russian recruit at the door and literally snaps his heels in front of him! That’s the German! - There is (apart from the hatred of some) the Russian’s lack of understanding of our mentality. It’s not always ill-intentioned, but it’s annoying. He is terribly suspicious and humourless. He forbids the currently popular hit song "Barcelona, du allein (you alone)..."[2] because Spain is a fascist dictatorship. When Opalev, an officer in the Russian camp headquarters, heard that we were fed up with captivity, he said he didn't understand! He drinks champagne like lemonade and cologne like schnapps. We are to eat as he does: dry bread with soup. (That's how the Russians eat it.) People with 2 suits are already capitalists, in his eyes. - There are the constant cheats on the rations. The potatoes have to be filled with a shovel instead of a fork so that as much sand as possible gets on the scales. Then he chases away the German rations officer, who is supposed to check the weighing, because he complained that Ivan had put his foot on the scales and put a stone on it.

Red Cross cards are given every 4 weeks, according to regulations - but they are not enough for everyone!

The wages, which are already manipulated downwards, are often not handed over. We are then told that it will be transferred to a blocked account and paid out when we are released!

We get winter clothes, but in return they take away our green Wehrmacht coats.

We are allowed to write letters, but they are often not forwarded.

Our house has piped water, central heating and electricity, but it often doesn't work.

And... and... and...

In consistent implementation of socialist egalitarianism, women's equality is radically carried out in the Soviet Union (except in the Muslim states). Women do the same hard work as men. But the brigadiers of the women's brigades are mostly men.

Magazine 19. Cereals are stored in this warehouse. Large stacks of sacks full of potatoes, millet, flour and much else. More rarely, a few sacks of sugar or the like. Our work consisted of unloading the lorries that brought these goods here from the goods yard and loading other lorries that then took the stuff out again to the individual state-run shops in the city. There wasn’t too much to do. The Russian guards would sometimes slip away, and the Russian nachalnik wasn’t always present either. When we had the opportunity, of course, we put aside some of the rations for ourselves. Every experienced plenny is prepared for such occasions. The bags must always be tight and without holes. It is also useful to have a small bag with you at all times. At present, I always carry a tablespoon with a broken handle on this command. It is easy to store and you can use it to take a spoonful from an open flour sack and put it in your mouth, for example, as you pass by. If you had to do it by hand, you would soon have smeared your hand and mouth and would be betrayed. The fact that the flour sack is open is because it “accidentally” fell down during unloading and burst open. There are other methods, but you must not do it often, because the nachalnik is not stupid.

In another case at another command, we agreed with the supervisor beforehand: We wouldn’t steal anything (called “zappzerapp” in German-Russian gibberish), and in return he would give us something voluntarily at the end. But not all nachalniks were so philanthropic, and there was often a beating if you were caught in “zappzerapp”. There was a lot of stealing everywhere, by Russians and Germans. It was like an epidemic. One comrade even told me that German prisoners of war were lined up with machine pistols in front of a food magazine because the Russians were stealing too much.

Once we unloaded a goods wagon on a siding of the passenger station. Among the goods was a sack of sultanas. While one of us carried the heavy sack, I went sideways to help support the load. As I did so, I poked my finger into an existing hole to fish out a few sultanas. But the sultanas were a bit frozen and hard, so I broke my fingernails. It was hardly worth it for the few sultanas I managed to grab. Besides, this was a risky venture, because when loading such treasures, as with sugar, there are always a lot of watchdogs (who, by the way, are all hoping to get something for themselves).

We stowed millet sacks in the large warehouse. From a sack that had opened, we filled our bags in unguarded moments. I had filled my haversack and went as inconspicuously as possible in front of the gate to put it in our lorry standing there. Next to the lorry stood our Mongolian guard. I wink at him and stow my bag in a corner. The Mongolian smiles. When we board the lorry to go home after finishing our work, my bag is gone. The Mongol is still smiling, the scoundrel!

Benno (von Knobelsdorff) had a different method. He simply let the loose millet trickle into his felt boot, namely the right one. At the end of work, the guard suddenly had us line up and sit down. We had to take off our boots and turn them inside out. Benno took off the (empty) left one. The Ivan wants to see the other one too. Benno puts the left one back on and wants to stand up, but the Russian makes him sit down again. Benno sits down and takes off the left one again. The Ivan didn’t realise. So Benno moved into camp with a somewhat swollen right foot.

We loaded sacks of potatoes. In the meantime, we had set up a fireplace behind the warehouse, over which our mess kits filled with potatoes were hanging. But the storage supervisor discovers them just as we are about to check whether they are already cooked. Like an enraged bull, Ivan came running, kicking at the mess tins like a football so that they flew off in all directions. Then he tramples out the fire with both feet and lunges at Hans Sölheim, beating him like a savage. Hans turns around and runs away. The Russian behind him. The rest of us go back into the hall, somewhat depressed by the loss of our meal. While we are still standing together a bit perplexed, we hear a loud “Hello, Camerati!” from the hall entrance. We turn around and look in disbelief at Hans Sölheim and the nachalnik, both walking arm in arm towards us. They laugh and wave. Less than a minute ago the Russian was still furiously beating him, now he is holding him in his arms, laughing! That’s the Russian mentality! I have experienced such sudden changes of mood several times. They can be fatal if the Russian is drunk and armed.[3]

Behind the warehouse lies a long end of telephone wire. You can always use something like that, and I roll it up. Then I notice that it's too long and Hans Sölheim, who is next to me, says, “Why don’t you tear off a piece?” I do. In the evening in the camp he says to me: “You committed sabotage today,” and when I look at him uncomprehendingly he continues: “The wire was a telephone line. I had pulled it down before!”

We unload peat trains at the western edge of town. The goods trains stop here and we simply throw the peat pieces down to the left and right onto the open meadowland. All with our hands, of course. Working with us is a brigade of convicted women and girls. When we complain that we have been imprisoned here for 2 years, they just laugh. 2 years is not a long time at all. After 5 years it would be hard, but 2 years? Nitchevo!

Close to the track begins the fenced-in area of a slaughterhouse. We see that every now and then a door opens and someone comes out and goes back in again. Some people have a nose for where there is something to get or where you can get hold of something edible. I've learned that a little bit. So I sneak up to the house through a hole in the wire fence until I reach the door. Here I don’t have to wait long. A sturdy girl in a blood-stained rubber apron steps out of the door. I shyly hold out my mess kit to her. She takes it from my hand without a word and goes back. After a short while she comes back and, with a dispassionate face, hands me back my cooking utensil, filled with fresh, warm blood. I leave with friendly thanks. Outside the slaughterhouse, behind the hall, we maintain a fire over which we immediately heat the blood in the mess kit. Within a few minutes we have a whole mess kit full of fresh blood sausage. Some take it back to the camp to sell it there. Later I worked at this slaughterhouse again for a few days, but in the administration building. There, too, we got a meal at noon in the canteen, but we sat alone at a table, separated from the Russians.

We are building a destroyed building (of the textile combine?[4]). The three-storey house is already finished up to the roof truss. Only the roof truss and some minor masonry work remains to be done. I am the brigadier of the unskilled labour brigade. We carry the bricks, 3-4 at a time, on our shoulders up 3 floors on foot. It's a grind, but we take it as slowly as possible. The nachalnik is a creep. Since he doesn't own a watch, he always asks me what time it is. But although I always give him the correct time, he always makes us work 1/4 hour longer because he naturally suspects again that I am lying to him. The consequence is that we are now really cheating him, and not only with the time.Since he won't let us leave the fenced-in workplace (which is not allowed either), I sneak away more often. As a brigadier, I don't have to work, but I'm not allowed to leave the workplace.

The outbuilding is also three storeys high. Since the partition wall between the two houses in the attic is not yet bricked, one can easily climb up to the attic of the residential house. I did so once to have a look around. There is a 10 cm thick layer of cinders on the plank layer of the attic. But the floorboards are not tight, and through the cracks I can see down into the kitchen, where the housewife is fiddling around on the cooker. I wonder why she doesn't notice the quiet trickle of cinders falling through the cracks on the kitchen floor. Or is she used to it?

I have stolen a few boards and climb back across the attic of the neighbouring house into the stairwell there. Here, starting on the 3rd floor, I knock on every flat door and offer my boards at the minimum price, as a special offer. But nobody wants them. They must get too many such offers. Finally, a woman on the first floor takes pity on me and gives me 4 potatoes for them.

A few days later I try again with a 2 m long log of 15 cm diameter. This time, however, I run across the courtyard to the next block of houses, always taking cover. But here too I am turned away everywhere. I simply have to leave the log in the hallway.[5]

Hans had discovered a tobacco shop not far from the photo shop (see below), only 100 m further down the same street. They had very cheap cigarettes and cheap tobacco. He kept this secret to himself and did a good business in the camp with a small mark-up. Then, when he fell ill, he let me in on the secret and described the location of the shop to me. Now I fetched the goods from there, and always a rucksack full at once. Once it took a little longer until I had stowed the numerous packages in the backpack and settled up with the woman. In the meantime, a queue of 6-7 people had formed. But they didn’t say a word and waited patiently until I was done, although they had certainly recognised me as a prisoner of war.

In the camp, Hans had a Landser who sold the cigarettes for him, for a 50% share. I wanted to earn everything on my own and sell them myself. And while Hans lay on his bunk and rested, I raced around the whole camp to sell my cigarettes. Hans had sold his entire stock, but I hadn't sold a single pack. I'm just not a businessman. Then I made an even bigger mistake. A clever comrade had been watching Hans' cigarette seller. He came on to me and I, in my harmlessness, told him about the shop and one day even took him with me after he had hypocritically explained to me that he was not interested in doing business at all. Since then, this crook is snatching everything away from us by buying in bulk and has spoiled the whole business for us. Hans has never forgiven me for my stupidity. Since then, our friendship has cooled down noticeably.

Flax Combine.[6] Since I’m talking about my stupidity: Here's another one right away that I got up to at the flax combine. We often worked near the kitchen here and naturally tried to get something to eat there. A whole number of girls worked in the kitchen under the supervision of a cook. Of course, the girls - as well as the whole population - were forbidden any contact with us. Nevertheless, the kitchen girls occasionally slipped us something. One day they had slipped me a whole portion of lunch. After spooning it out behind a screen, I guilelessly walked up to the counter with my empty plate and handed it to one of the girls with a loud “bolshoi sspassiba[7]!” The girl cast a quick glance at the cook, her nachalnik, then looked at me reproachfully and wordlessly took the plate from me. The cook pretended not to hear. Anyway, I quickly disappeared from the canteen. I idiot!

In a room next to the kitchen was a sewing room where about 10 girls were employed. Günter Heuer often appeared here. Boyish and cheerful, he came whirling in, gibbering in Russian with the girls so that they shook with laughter. He was certainly their crush.

There was a pile of rubbish behind the kitchen, where I discover a small carrot that is still fresh. I pick it up, wipe it off and eat it. I was annoyed about this for a long time. I haven’t sunk so low that I have to eat from a rubbish heap.

Brickyard. It was located quite far outside the town on a broad, flat-arched plateau, free and open in treeless terrain. It had been destroyed in the war and is to be rebuilt. The path to it leads across the bare plateau. The unusually cold winter blows the icy wind through our clothes, making us shiver to the core. If we have to stop once, we fear freezing to death. Even the walk to and from the camp is a torture, and the work at this windy altitude is hard. We were laying bricks and mixing mortar at -20°C, because the Russian engineer had to meet his target: According to the plan, production should start in spring. So despite the cold, we just kept on bricking, and when not enough bricks came, we tore off the lower layers of the metre-thick ring wall of the kiln and bricked them back on top. It’s unbelievable, but the engineer had only one goal: He had to meet his norm, keep to his schedule, because production had to start in the spring. If something went wrong then, it was no longer his business. He had fulfilled his target.

About 100 men worked at the brickyard. The detail was extremely unpopular and dreaded, because there were many casualties due to illnesses, colds and frostbite.

|

Editorial 1938 1939 1940 1941 1942 1943 1944 1945 1946 1947 1948 1949 Epilog Anhang |

|

January February March April May June July August September October November December Eine Art Bilanz Gedankensplitter und Betrachtungen Personen Orte Abkürzungen Stichwort-Index Organigramme Literatur Galerie:Fotos,Karten,Dokumente |

|

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. Erfahrungen i.d.Gefangenschaft Bemerkungen z.russ.Mentalität Träume i.d.Gefangenschaft Personen-Index Namen,Anschriften Personal I.R.477 1940–44 Übersichtskarte (Orte,Wege) Orts-Index Vormarsch-Weg Codenamen der Operationen im Sommer 1942 Mil.Rangordnung 257.Inf.Div. MG-Komp.eines Inf.Batl. Kgf.-Lagerorganisation Kriegstagebücher Allgemeines Zu einzelnen Zeitabschnitten Linkliste Rotkreuzkarte Originalmanuskript Briefe von Kompanie-Angehörigen |

- ↑ This photocopy is the only example of its kind. All originals of the author’s postcards have been lost.

- ↑ Barcelona, 1943, music: Franz Wilczek, lyrics: Inge Wolf

- ↑ Cartellieri p. 340 refers to the Russian concept of the “wide soul” (широкая натура).

- ↑ possibly the houses of the factory "Kalinin" at Vitebsk Chaussee 46-50, which were built by Germans in exactly this period (message by Anna Shukova on Facebook)

- ↑ The paragraphs "Photomaton" and "Easter/Cemetery Visits" that follow here in the original text were saved under the appropriate dates 8 Dec 46, 2 Nov 46 and 1 Nov 47, respectively.

- ↑ On the site of the former textile or flax combine now stands the shopping centre “Galaktika”.

- ↑ большое спасибо, thank you very much!