5. Juli 1947

5 July. Large working brigades or also the combination of several smaller brigades are called companies. Of the 13 officers in our camp, 6 are assigned as company leaders, including myself. After 2 years of belittling the officers’ reputation among our soldiers, the Russian now wants to use the officers’ authority to increase the work output of the brigades.

Since I am no longer a full-value worker due to my loss of strength, I am employed in the camp as a officer of night duty. My most important task is that of a fire watch and the control of the house and the dormitories at night. During the day I am off duty. At night I sit downstairs in the former porter’s lodge. There I discovered a thick German Bible, in which I read for hours.

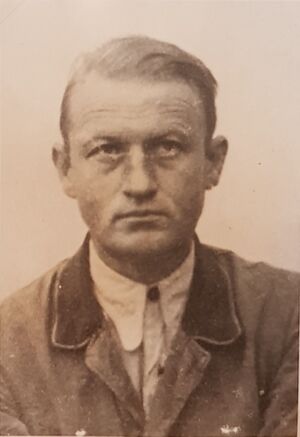

All camp inmates are photographed. They say it’s for a central prisoner file in Moscow. My porter’s lodge is converted into a darkroom for a few days and nights. I watched the photos being developed, and when my picture was done, I had an extra print made, which I sent home some time later (photo here).

During one of my inspection tours, at dawn, I also come into the yard. There comes an Ivan with a ladder, puts it against the wall of the house and takes out a young one from one of the House Martin nests. When he sees me, he lets it fly and asks me, “Yeto lootche, karacho?”[2] I shake my head disapprovingly.

We officers have been given our own sleeping quarters. Until now we lay with another 100 men in the large cinema hall, which receives almost no daylight. There we lay on completely lice-ridden three-storey wooden cots, where we searched our clothes for lice before falling asleep and then several times during the night, in the dim light of the constantly burning bulbs. The air in the room was completely stale.

Now we 13 officers lie in a smaller room that has a large window to the outside. The room is bright, clean and airy. It even has central heating, which works most of the time. We are thus also separated from the enlisted men - as the regulations require.

In the corresponding room below us, one floor down, are the WK people. I was supposed to give them a lecture one day. I wanted the camp leader Max Gasmann to be there too. But he didn’t come, and after a longer wait the lecture was cancelled.

A Jewish commissar inspects our new living space. He sneeringly points at our socks hanging over the radiators and the tin cans that serve as containers for all sorts of things. His final spiteful question: “Is that German culture?” It was a disgusting type. That’s easy for him to say. First they steal everything from us and rob us blind, and then they laugh at our primitive substitutes. They cram the rooms full of prisoners and then criticise the lack of hygiene.

I exchange a set of fine sewing needles at the camp tailor (Antifa member) for half a ration of bread. Pretty shabby. I would have expected more.

We currently get small anchovies (sprats) as a bread topping which always have to be prepared first. Hans Sölheim always gives me his ration because he prefers to rest on his cot instead of cleaning them out. He has a different lifestyle than I do. While I prepare the extra rations I bought outside, peel potatoes and run to the boiler room to have something cooked, he lies on his bunk with peace of mind. Who is more energy-efficient, more economical, more rational? That is an important question here.

I make a remark that Herbert Wolfslast (a very sympathetic former artillery lieutenant) completely misunderstands. He suddenly snaps at me, and in my stupor I make matters worse. Our relationship is soured by this.

My function as night officer has another advantage: in the morning, after all the work detachments have marched off, I get a second helping from the kitchen. Today it’s fish soup. The mess kit is full to the brim. But it's really just fishbone soup. I always take a mouthful of soup, suck out the liquid and spit out the bones. The food is never very good, but the cook seems to mean well with me.

There’s a Saxon in the camp who has even made a fool of himself among the Landsers because of his gluttony. After the food is served, there’s usually still some left in the kettles. So anyone who is willing or able gets a second helping while stocks last. This Saxon now devours even the hottest food in no time at all near the kitchen and then runs to the counter again. By the way, he also plays the violin in the camp orchestra. But he is unmusical, plays stiffly, dryly and without sensitivity, like a wound-up music box. When a Landser once teased him, he replied majestically: “You have no idea what I’ve already done for the arts!”

We’ve been moved again. We are now lying together in a larger room with 30 men. Next to me on the upper cot lies Wolfslast. He is missing a stocking. As I happen to have a single one left, I give it to him.

The food is pure water soup again. The result is that I have to go out three times during the night. That means climbing down from the upper bunk, walking down 2 floors to the toilet facility in the yard and the same way back, and this three times in the night.

I have an upset stomach, sleep fitfully, have to keep getting up to burp. These constant interruptions of sleep, together with the plague of lice, ruin the body even worse than the work.

We have a funny fellow among the officers. He was something like a paymaster in a police unit and is considered an officer. Now he is a brigadier. He is dividing the bread ration for his brigade. He has been chopping the ten portions for a full hour and can’t manage. The pieces are getting smaller and smaller. Either he is too stupid or he wants to cheat. But two men from his brigade stand silently and patiently next to him and don’t let him out of their sight. He is an unfortunate unicum. He talks fast and bubbly, constantly slurring his words, has a primitive mental level, is clumsy in his expressions and in his dealings with his comrades, and therefore constantly offends, makes himself ridiculous and unpopular. During a conversation he asked me to draw his attention to it if he should behave so strangely again. I did not have to wait long for such an opportunity. When I pointed out his behaviour as requested, he hisses at me angrily, “Now you’re starting to pick on me, too!” That’s how it is! I resolve never to do anyone such a friendly service again.

A fellow officer, an elementary school teacher in his civilian profession, paints the Red Cross cards with pretty little motifs. He is paid a small fee for this. I learn from him a bit and then paint my own cards to send to Carola. 2 originals still exist.[3]

|

Editorial 1938 1939 1940 1941 1942 1943 1944 1945 1946 1947 1948 1949 Epilog Anhang |

|

January February March April May June July August September October November December Eine Art Bilanz Gedankensplitter und Betrachtungen Personen Orte Abkürzungen Stichwort-Index Organigramme Literatur Galerie:Fotos,Karten,Dokumente |

|

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. Erfahrungen i.d.Gefangenschaft Bemerkungen z.russ.Mentalität Träume i.d.Gefangenschaft Personen-Index Namen,Anschriften Personal I.R.477 1940–44 Übersichtskarte (Orte,Wege) Orts-Index Vormarsch-Weg Codenamen der Operationen im Sommer 1942 Mil.Rangordnung 257.Inf.Div. MG-Komp.eines Inf.Batl. Kgf.-Lagerorganisation Kriegstagebücher Allgemeines Zu einzelnen Zeitabschnitten Linkliste Rotkreuzkarte Originalmanuskript Briefe von Kompanie-Angehörigen |

- ↑ Summer 1947 acc. to inscription on the back of the photo, July acc. to classification and inscription in the diary text or August, if it is the photo mentioned on the Red Cross card of 20 Jan 1948 as having been taken in the camp - and the month was still correctly indicated at the time, after all half a year after the photo was taken

- ↑ He probably said, «Я отпущу, хорошо?» I let go, good?

- ↑ In the collection there are three painted cards, dated 10 Aug and 15 Nov 1947 to his wife Carola, which, however, were probably still painted by the aforementioned comrade, as the author explains in a later card, and one dated 25 Mar 1948 to his parents; he explicitly described the latter as being painted by himself.