31. Dezember 1947

Mail written on the 10th is returned on the 31st. The censorship had not let it pass.

According to orders, there was an increase in rations on 1 January. But only after this had leaked out to us prisoners of war do we receive, after much toing and froing, more bread, pepper(!) and bay leaves(!). But in return they took away other products (flour, millet, potatoes), and we get less soap! So these crooks have turned the intended improvement into a deterioration. In fact, I have repeatedly had the impression that the Moscow leadership is trying to maintain our labour force by providing us with sufficient food. That would be sensible and to their own advantage. But these measures were thwarted by corrupt Russian camp commanders and “German” camp leaderships who sold large quantities of rations, exchanged them for inferior ones and pocketed the profits. According to Soviet law, these were serious crimes.

Once again investigations after SS tattoos. Only now did I learn that the SS men had a small tattoo on the inside of their upper arm. Examination by a Russian doctor and the political commissar.

The picture-perfect Russian camp doctor who had retrieved us from Riga and who had been the camp doctor here until now, disappeared. Rumour has it that she had a fling with our camp barber (a German prisoner of war), a handsome guy.

The current doctor is fat and ugly, but she takes her job seriously and sometimes stands up for us. She is Jewish. Once she forbade outdoor work at -25°. During one of the vaccinations, which were given at longer intervals, I sneaked out of the treatment room. But she noticed. I had hardly reached our living room before she had me brought back.

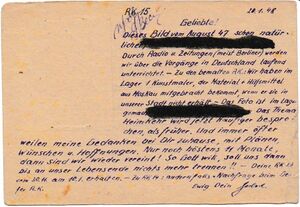

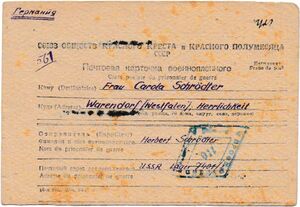

We found Red Cross postcards that had been used as notepads and scribbling paper.

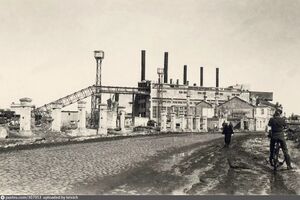

Electricity Plant. The electricity plant is located in the middle of the Lower Town, the part of the city situated in the Dnieper valley, and right next to the railway tracks. Some of these tracks lead into the plant. The plant is still partly destroyed. That is why there are two large American Pullman cars on the site, their engines or motors running day and night with a great roar to generate additional electricity. Whether they are generators or just drive generators is beyond my poor technical knowledge.

Our work here mainly consisted of constantly supplying the machines in a multi-storey building with fuel. So we were constantly unloading goods trains that came in with peat or sometimes coke. The pieces of peat are as long and thick as a strong man’s upper arm. They are as hard as wood. When unloading, we simply throw the peat down on the ground to either side. From here it is taken by a small trolley track to a conveyor belt with excavator shovels (bucket elevator), which carries the peat diagonally up to the 2nd floor of the engine house and dumps it there.

••• S. 329: Flashback, not datable, move to 1946/August/6 after publication •••We had already worked here for several weeks in summer. The day shift was bearable, just a bit dusty. Sometimes, however, the peat trains came in such close succession that we had to work around the clock. Then the day shift would continue working as a night shift, or it would be replaced by another brigade that had already done its day work elsewhere.

I remember one of many similar cases: Right after dinner we set off again, tired and angry, because we had already done our day’s work. The train is at the usual place, to the right and left the elongated hills of peat unloaded from the previous train. We climb onto the wagons and start throwing down the pieces of peat. With our hands, of course. And in the dark, of course. We toil all night long. As it is warm, we work bare-chested. In the pale light of the dawning morning, we can make out the peat hills on either side of the train, piling higher and higher. But the work is getting slower and slower. We are tired and dusty. Now the wagons are empty, but so much of the peat mounds has slid onto the tracks that the train cannot leave. So we have to crawl under the wagons to clear the tracks, but no one has the desire or strength any more. The nachalnik keeps driving people under the wagons. We need almost 2 hours for this work, which is usually done in 1/2 hour. Finally, finally we are done. The train jerks off and slowly rolls away as we make our way back to the camp where, after a short breakfast and a rest, we start our day’s work again.

A Russian nachalnik beat a prisoner so badly with a truncheon that he had to be taken to hospital with broken bones. Always the same: beatings and chicanery.

The replacement is already there, but the old shift has to continue working, without extra percentages, of course. We react with fraud and theft. Once they carried a supposedly sick person out of the power plant on boards and then sold the boards.

We are on our way back from the workplace to the camp and are just marching past the railway station. Since the cobblestones are bothering my tired legs, I walk alongside the column on the smooth sand path (the sand path is the pavement). On the way, a Russian officer comes up to me. He stops me and tells me to march in the column. But I play dumb and pretend not to understand him. Then he gives up and goes on. So do I, on the sand path of course.••• S. - end of flashback •••

Now it’s winter, and we’re working at the electricity plant again. On the way here we always pass a church, which stands on the other side of the Dnieper on the southern slope of the valley. It is, of course, closed, and so it stands somewhat lonely on the open, snow-covered slope. But its gilded domes, crowned with golden Russian crosses, rise bright and shiny into the clear blue winter sky.

Near us, Russian prisoners work. They are loading peat into the tippers. A sergeant of their guard pokes into each peat tipper with a pointed iron bar, for a prisoner might be hiding under the peat in order to escape.

We haul coke. It lies in man-sized black mountains on the white snow. We shovel it into baskets, which we carry 50 metres further and pour into tippers. From here it is taken to the lift. One part of our brigade shovels the baskets full, another carries them to the tippers. Tonight we are assigned a woman who obviously has to do some punitive work. The Russian nachalnik is very spiteful to her. She doesn’t seem very robust and does her work silently and humbly. I fill her basket a few times and she slowly walks with it to the tipper. I feel sorry for her. I say it to Hans, but he is harsh. “Every Russian woman who goes kaput doesn’t give birth to any more Russians!” is his reply. While we retire to a small building for dinner, the woman remains sitting outside in the cold. We have no food left, for it is meagre enough. But I go out to her. She is squatting on a basket with her head resting in her hand. I stroke her cheek once, but she doesn’t react. Then I go back, because the disgusting nachalnik is already arriving again. The next day the woman doesn’t come back.

The atmosphere in the camp improves somewhat. Max Gasmann, the camp leader and officer-hater, even shakes my hand. I think the news from home and reports about beginning comrade grinder trials at home are making them a bit thoughtful after all. Unsocial brigadiers are dismissed.

|

Editorial 1938 1939 1940 1941 1942 1943 1944 1945 1946 1947 1948 1949 Epilog Anhang |

|

January February March April May June July August September October November December Eine Art Bilanz Gedankensplitter und Betrachtungen Personen Orte Abkürzungen Stichwort-Index Organigramme Literatur Galerie:Fotos,Karten,Dokumente |

|

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. Erfahrungen i.d.Gefangenschaft Bemerkungen z.russ.Mentalität Träume i.d.Gefangenschaft Personen-Index Namen,Anschriften Personal I.R.477 1940–44 Übersichtskarte (Orte,Wege) Orts-Index Vormarsch-Weg Codenamen der Operationen im Sommer 1942 Mil.Rangordnung 257.Inf.Div. MG-Komp.eines Inf.Batl. Kgf.-Lagerorganisation Kriegstagebücher Allgemeines Zu einzelnen Zeitabschnitten Linkliste Rotkreuzkarte Originalmanuskript Briefe von Kompanie-Angehörigen |

- ↑ with friendly permission from Александр Захаров