5. August 1947

| GEO INFO | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concrete plant | still to be localised | |||

| “Kalinin” factory | ||||

| Scrapyard | still to be localised | |||

5 Aug. The back pay was made up by simply cancelling the 5 months in question.

In the last 2 weeks, 2 men collapsed again. One at work, one on the way to work.

Whole brigades are breaking down from hunger and weakness, gradually collapsing (brickworks, boilermakers) because the rations are not sufficient for the heavy work. This is no longer exploitation, it is almost murder.

The “German” camp leaders have neither interest nor understanding for the men’s concerns. On one of the few Sundays off, people wanted to sleep but were forced to participate in sports. - A Landser wanted to raise a question when the gentlemen of the anti-fascist camp leadership, perfumed and ready to go to town, declared: “Leave us alone with the work stuff now!”

Often no electricity (concrete plant), no material (factory). Therefore no production, therefore no percentages - and no bread!

August 47. Cabbage and cucumber soups. The number of people unable to work increases rapidly. Consequences of hunger, phlegmons, skin rashes, boils, loss of teeth. Doctors cannot help. No medicines, no bandages. Either nothing is supplied or the Russian embezzles it. But there are also cases where the doctors have stolen bandages, take green medicines to dye clothes or use Prontosil as ink.

We now have a dental ward in the camp. The condition of the prisoners’ teeth is abysmal. When at last the urgently needed material was delivered, one of our plennis, a dentist, was appointed. Now all the Iwans belonging to the camp arrived with their families to have their rotten dentures repaired. The waiting room was full of Russians, who of course all had to be treated free of charge. And when they had all been served, the material intended for the prisoners had been used up. Our Landser can continue to torture themselves with their toothache.

Concrete plant. The whole “factory” consisted of a concrete mixer, a 3 m high press and an office shack. The factory area was 50 x 80 m. Here we produce building blocks. In the concrete mixer, a mixture of cement and slag is produced and poured into the press, which then presses the mass into large-sized building blocks. We then carry 3 bricks at a time on a board to an open area where they are placed to dry. In the process they become hard, because when they come out of the press they are still wet, soft and heavy.

End of work. Hans cleans the mixing machine, and since no one is around at the moment, he bangs the rivets of the drum with his hammer in massive blows. But one of the brigade noticed and reports the “sabotage” to the camp. Strangely enough, nothing happens thereon. A few days later, in a harmless conversation with this denouncer, I try to find out his name and home town. But this fox is cautious and gives nothing away. But I think he was from the western Havelland or from Brandenburg or Burg near Magdeburg.

End of work. It is already dark and we are waiting for the lorry to take us to the camp. There is a lorry next to the office. There are a few baskets of apples on it. Lieutenant X stalks up, climbs up and grabs some apples. But he gets caught and, one more time, gets a few mighty slaps in the face. He’s always unlucky, since Michai on the wire-roll detachment once gave him some too.

While we are working on the grounds of the concrete plant, an elderly woman comes by and hands Hans a whole loaf of bread through the fence. There are many good people also among the Russians.

We get home mail. When they hand it to us, it is only the empty envelopes.

There is no account of those who have died. We are not allowed to register them privately either.

In the concrete plant, the standard is raised. Previously 800 bricks a day with 13 men, now 800 bricks with 8 men. Additional night work without pay and without additional rations.

Continuous work accidents due to inadequate occupational safety, e.g. loading work at the goods station at night without light.

Comrades recount:

Coal mine in Stalino 1944: coal hewn lying in a low seam, the pieces of coal brought out crawling backwards. Norm: 1 tipper a day per man. After 2 months everyone was sick. Of 1600 men, 267 remained alive. - Stein (from Thorn) recounts: His group with 1 officer led off as prisoners. The officer running at the end of the group was shot. Great thirst, come past river, whoever ran to drink was shot. - Marx (Totengräber kommando Vitebsk): Of the 22 men in the kommando, only 4 men remained. - In 1944, 1800 of 2200 camp inmates died. He himself buried 1325. - Tolksdorf: On the day of the surrender of Königsberg one could hear everywhere the desperate screams and the horrible screeching of German women who tried to defend themselves against the rapes by the Soviet soldiers. - In Metgate(?)[2] the population was rounded up and blown up with mines. He himself buried 176 women and children there. - Dec. 44 and Jan. 45 in Jarczuz(?): Out of 1300 officers, 150 died. - Transport home from Gorki: The population is very unfriendly. (The Germans had not penetrated this far in the war. The population saw them only as prisoners of war and had been completely outraged by Soviet propaganda). - A Russian officer had a Landser show him how to eat with fork and knives. - Werner Kiesel talks to a Russian woman who was in Auschwitz. She gives him half a laundry bag full of potatoes (about 5 pounds). - Detachment from Kovno: Lithuanian friendly. Epidemic of dysentery in the camp. Within two months 700 men die - Bormann (Kaunas): Telephone line to Russian captain cut. - Theo Korth (Kosch?): Because he refused blackmail for informer services, he was given standing and water karzer (a narrow dungeon where he stood up to his stomach in water). - German girls shorn. - Rückkämper: The village echoes again with the cries of pain and despair of German girls. - Red Army soldiers beat and murdered German wounded. - (?) Chased wet and naked into the cold after sauna bath: 1 dead. - Adler (Borisov) and Klettendorf (Breslau): All accessible women rounded up in a house and raped continuously. - An old CP functionary has to watch his wife and 14-year-old daughter being raped. As an old communist he goes to the Russian commander and complains. He is shot. - 27 women commit suicide to avoid being raped. - Adler’s wife has all her front teeth pulled out with pliers to look ugly. (Adler is a communist!) - Benno, Kade, Rolf (Dresden-Neustadt): Heartbreaking, shrieking cries for help from women. German officers go to the camp gate to come to the women’s aid. The red guard holds them back with his rifle aimed. - A coal wagon shows a message written in chalk on the wagon wall: Greetings from Marie and Erika, coal district, shaft 6 - Sloboda: During a frisking, a man is found to have 3 boxes of matches. He is put in karzer on suspicion of sabotage. - Tula: German, shorn girls are loading stones. Called from the camp fence, but they do not answer. - Exiles are often held for years after their time is up. Or released and immediately arrested again. - After the occupation of Silesia: A clergyman happens to notice that a girl is wearing no briefs. To his reproachful question she replies, “No use, Russians keep coming and wanting something!”. - BVK[3] (Borisov): 20 Hungarians locked in darkroom for only 7, for failing to meet standard. They scream and shout. - Russian doctor transferred for being too good to Germans. - German monitoring service listens in (during the war) on the interrogation of a German prisoner of war: “1 and 2 applied (= pulling out finger and toe nails), nothing revealed.” “Go on, take him to the battalion. I expect him not to arrive here.”

End of comrade recounts.

In Smolensk, many people still have to fetch their household water from the street wells, just like in the villages. - Women carry their children on their backs. - Loads are often carried in bundles on the back. - Most trucks are still started with a crank instead of a starter. - It is not meant in a derogatory way, but it is Europe 100 years ago.

Factory “Kalinin”. It lies directly below us on the flat slope and already reaches into the valley. It is only separated from our camp by a fence, because our “Palace of Culture” was in fact the meeting house of this factory. The small factory has several departments: Tractor repair shop, boiler shop, moulding shop and foundry. I am a brigadier of a work brigade in the factory. We work in all the departments in turn, as needed. In between we get a command in the city again, often for months. The factory has railway sidings.[4]

In socialist Russia, too, the merit principle rules, and there is no talk at all of a classless society, except in propaganda. Specialists (skilled workers) are paid far better than unskilled workers. The difference between these two wage groups is much greater than in western countries.

In the boilermaker’s shop we struggle with the crawler track of a big tractor. The lead-heavy chain has to be moved from one workplace to another. This is done by six of us pushing between the chain links with crowbars and then levering it on centimetres at a time. This is how primitive work is still done here in many cases. In the boilermakers’ forge, everything is hard, back-breaking work. Even the thick steel plates for the boilers are formed by hand by the prisoners of war with heavy hammers. This is where many of them flag.

Things are a little quieter in the moulding shop. Here, some are skilled workers, moulders, Russian and German. (Skilled workers were always in demand. They are better paid and often treated better). The floor of the large hall was laid a little lower and then filled with a thick layer of dark, loose special earth. The moulders then modelled cavities into this floor and covered the top with earth. These cavities have the shape of certain devices or machine parts. Now the foundrymen approach. Two of them carry the casting material on a long pole with a bucket of molten iron hanging in the middle and carefully tip it into the mould through a hole that the moulders had left open. After a few days, the iron has cooled and the cast part has hardened. Now it is dug out and has to be cleaned and sanded. This work is then done by the cast grinders. This whole method of working is still primitive, but it works.

At the moment my brigade is working in the moulding shop. We roll a millstone into the hall with 3 men. The stone disc has a diameter of 1 1/2 metres and is 15 cm thick. On the soft floor of the foundry it suddenly loses its vertical balance and tilts to the side. I shout “hold on”, but two men had already jumped to the side. I grabbed it, but the man next to me, a young lieutenant, faithfully refused to let go of my order. With two men, however, the stone could not be held. It begins to tip and before we can jump back, the edge of the millstone falls on the lieutenant’s toes. He pulls his leg up, holds it up with both hands and hops around in circles with pain, on one leg. The toe was broken, but it had still come off lightly because the soft ground had given way and pressed the foot into the earth.

A Russian girl and a German prisoner of war are caught in an adjoining room of the moulding shop in a clear position. The girl is gone.

In the tractor factory, the repair of a tractor has just been completed. Now it is being given a nice coat of paint. The spokes are red, everything else green. I stand next to it and look at the pretty machine. Another piece of a Potemkin village. I overhear the conversation of the two Russians, who are a little worried about the durability of their repair. They are expecting the tractor driver to come and pick up his vehicle himself to take it back to the collective farm. He does indeed arrive and immediately begins to try out the tractor in the factory yard. While he drives around the factory grounds, the Russian foreman sweats blood. Because as long as the vehicle is not shipped, the factory still bears the responsibility. But the tractor driver is satisfied. He drives the tractor to the railway track, where it is loaded and lashed down. The Russian master breathes an audible sigh of relief. His standard has been met, and if the tractor breaks down again tomorrow on the collective farm, it’s not his fault.

Half of my brigade is sent to a scrap yard to clean up among the wrecked cars. The place is near the factory and I go with this group for a few days to see the working conditions there. We are guarded by a Russian woman, medium height, roundish with red chubby cheeks. She is kind-hearted and the long shotgun she has shouldered does not suit her at all. She often brings along her 12-year-old son, who is the spitting image of her. It’s funny how much they look alike. The woman often lets me go out shopping, and then I am out in town for hours. My brigade doesn’t work themselves to death either. But it’s still not a pleasant detachment, because it’s bitterly cold. So after a few days I go back to the other part of my brigade, which works in the boiler shop. Here it is warm. Later, when I came back to the scrap yard, the guard woman sulks with me. She was offended because I didn’t stay with her detachment. Didn’t I like it with her? Of course I liked it. She was always very friendly to us and bought a lot of things from us, even though she didn’t need them. She only did it to help us. She was the typical good Russian mother.[5]

Brigadiers don’t have to work. Nevertheless, I often did it because I quite like working. But now I do it less often and therefore have a lot of freedom of movement. Wolfslast leads another brigade in the factory. Sometimes we meet on the factory premises and talk for a while.

One day, shortly before closing time, our pilot officer and room-mate presses a small package into the hand of his brigadier Wolfslast with the request that he take it to the camp. Wolfslast takes it unsuspectingly and also passes through the camp gate. (When leaving the factory, the detachments are often searched, only the brigadiers are usually left unscathed). Upstairs in the parlour, the airman had the parcel handed back to him. It contained valuable material that the Austrian had stolen. This trick was a bottomless meanness, because if Wolfslast had been caught with it, he would have had to expect a severe sentence, because the factory with all its material is state or collective property. In theory, according to the socialist understanding of the economy, it belongs to the people. And theft of people’s property is therefore a crime against the state and the people. It is always harshly punished.

I am sent alone to the factory director’s house to mend a garden fence. In the courtyard are two armchairs with red plush and broad gold fringes. Mrs. Director in a black silk dress. All a bit ostentatious and all German loot. I wanted to use the director’s loo. It is the well-known wooden house in the garden. But my plan ran into difficulties. Both seats were wet and literally sh... The remains of human digestion protruded from the seats in a pointed hard frozen cone. One had to climb onto the seat and perform one’s function in a squatting position.

Later, another prisoner of war gave piano lessons in the same house and then also ate at the table during meals. The cutlery was marked “Hotel zur Post”. Probably the piano had also been stolen in Germany.

In the meantime I was given a new command. On the way back to the camp, we met a column of Russian prisoners on the Dnieper bridge. They are more closely guarded than we are. Their guards have dogs with them. When the guards see us, they get nervous, run along their column and shout. They want to prevent us from talking to each other.

August 47. A German prisoner of war has escaped from a collective farm on a tractor. He speaks Russian well. Maybe he’ll get through.

The “Tägliche Rundschau” reports back home that there is a prison camp in Leningrad without barbed wire. A week later a third fence is erected around our camp. - Saxon daily newspapers tell their readers that we get 800-1000 g of bread per day.

Our forest camp has no shoes and ragged clothes with 10-12 hours of work.

Another big meeting with the topic: How can grievances be remedied? Where can improvements be made? The Russian makes big promises, but nothing is done, as usual. Apart from all the other harassment and cheating, there is a fundamental grievance: The labour standards have been set under normal conditions, that is, that there are materials, tools and healthy people. But in our factory and in most other workplaces, none of these are present. Therefore, the norm (100%) is normally hardly achievable.

Last year at this time we got 900 g of bread and 800-1000 g of soup. This year it is 600 g of bread and 600-750 g of soup. And this is only with norm fulfilment of 100%! And on top of that, individual labour demands are being increased. And the good German still slaves and drives each other, because if 1 or 2 men are lazy, they depress the whole norm of the brigade. So the underperformance of one or a few people harms the whole group. Therefore, they are then often driven by the other brigade members. A clever system!

The German is the best soldier in the world, but also the best prisoner!

The militia (police) becomes more vigilant. Prisoners of war who are caught shopping or strolling around in town are taken back to the camp. Usually that settles the case.

The Russian locks us in rooms too small and doesn’t give us lockers for our clothes. But he demands order and cleanliness. He takes away our clothes, sometimes shaving things, but demands tidy clothes and shaving. He himself spits and poops everywhere, but he criticises us for every crumb of dirt.

|

Editorial 1938 1939 1940 1941 1942 1943 1944 1945 1946 1947 1948 1949 Epilog Anhang |

|

January February March April May June July August September October November December Eine Art Bilanz Gedankensplitter und Betrachtungen Personen Orte Abkürzungen Stichwort-Index Organigramme Literatur Galerie:Fotos,Karten,Dokumente |

|

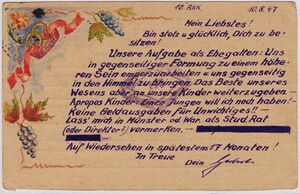

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. Erfahrungen i.d.Gefangenschaft Bemerkungen z.russ.Mentalität Träume i.d.Gefangenschaft Personen-Index Namen,Anschriften Personal I.R.477 1940–44 Übersichtskarte (Orte,Wege) Orts-Index Vormarsch-Weg Codenamen der Operationen im Sommer 1942 Mil.Rangordnung 257.Inf.Div. MG-Komp.eines Inf.Batl. Kgf.-Lagerorganisation Kriegstagebücher Allgemeines Zu einzelnen Zeitabschnitten Linkliste Rotkreuzkarte Originalmanuskript Briefe von Kompanie-Angehörigen |

- ↑ From the preface: I cannot necessarily vouch for the truthfulness of the "Comrades recount" sections. With such reports, exaggerations and pomposity on the part of the narrators cannot be ruled out, although I personally do not doubt the truth of these reports in principle from my own knowledge and experience.

- ↑ In the Kurrent script used by the author, Mothalen is written similarly

- ↑ Is this perhaps: Bruderbund der Kriegsgefangenen, antifascist underground organisation of Soviet prisoners of war 1943-44 (Für immer gezeichnet: The Story of the Eastern Workers. Translated from the Russian by Christina Links and Ganna-Maria Braungardt, Ch. Links Verlag, 2019)

- ↑ The factory still exists. In the Palace of Culture (“Club for Workers of the Kalinin Plant”) there is now a legal academy. A railway siding is not detectable now, nor on wartime aerial photographs or city plan; however, the plant is next to the railway station, separated only by the main road.

- ↑ This woman could be identified by support from the Facebook group “Другой Смоленск” as Mrs Артюхова (Artyukhova) with son Юра/Юрий (Yura, diminutive of Yury). According to them, the author was downright friends with her, taught the son a lot, and she hoped he would take her with him to Germany. She never married.