20. Februar 1943

| GEO & MIL INFO | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

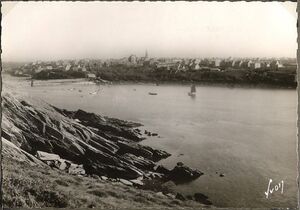

| Le Conquet | ||||

| Saint-Renan | ||||

| Brest | ||||

| platoon leader again (heavy mortar platoon) sector commander of Götterbucht CoyChief: Degener | ||||

The regimental commander, Lieutenant Colonel Haarhaus, has announced a survey of our positions in Götterbucht[2].[3] This section is under my command. To greet the commander, the officers of the battalion have planted themselves on the beach. Six manikins, neatly aligned in line, stand in the sand of the empty beach awaiting the commander. It is a picture to laugh at, but the stiff commander wishes military forms to be preserved. When he arrives, he is reported in accordance with regulations. Then I have to step forward specially and report my promotion (in a prescribed formula[4]), which he signed himself at the time. Then he congratulates me. Now the inspection begins.

According to regimental order, I had resigned from the battalion staff and returned to my old company as platoon commander. Then, as section commander, I took over the defensive positions of the Bay of the Gods in this coastal strip about one and a half kilometres long. In my section there are two 7.5-cm guns (Kampfwagenkanone), four heavy machine guns and four heavy mortars. The firing positions are partly single, partly grouped together, each surrounded by a ring-like wire entanglement and furthermore protected by a continuous wire entanglement in front and in the rear along the entire length of the section, with the particularly endangered points being additionally protected by mine obstacles. My command post is located in the sturdiest strongpoint in the bay. It is equipped with four mortars and two heavy machine guns, has a concrete bunker and two small living barracks where I live with the operating crews. The barracks are sunk so deep into the earth that only the roofs protrude a little above them. It is a quiet time. Although there is a stiff breeze up here on the cliff and it is also rainy, it is not cold. Besides, we have enough heating material. During the day we dig our trenches and improve the positions, and in the evening Obergefreiter Willi Neuhaus entertains us with his dry humour. Neuhaus, like all the others, is a true Berliner and a beer hauler by trade. I’ve repeatedly wanted to propose him for non-commissioned officer, but he refuses any promotion. Like him, all of us here are old, proven Russia warriors and have done their duty in many battles and fights. They don’t love war, but they endure it with equanimity and Berlin brashness. At least on the outside. They stick together in loyal comradeship, and there is no doubt that they will continue to do their duty, right to the end.

There’s only one I don’t like. It’s a new guy who came with one of the last batch of recruits. A young, strong guy who would have made a good soldier. But he doesn’t want to, is lazy and reluctant. I’ve already spoken to him calmly in private, but he won’t change. His name is Hargesheimer and he is from Friedrichshagen[5].

Every other evening I send a man to Le Conquet to fetch extra dinner from a hotel there. The portions he fetches in our cookware are small, but it is an extra hot meal. It costs 1 mark. Once I send a man into the hinterland for a whole day to organise extra food. The guy stays away for two full days and then comes back empty-handed. He says he had to find the sources first. Now he knows where to get something. So I let him go again. This time he stayed away for three days and then returned with a few sausages, just enough for a finger-length piece each. I never let that crook go away again.

Today we continued to work on improving our positions. As always, I diligently joined in the digging because I enjoy it. I was so absorbed in my work that I didn’t even notice the rain that was quietly starting. But when I gradually got wet and looked up, I realised that I was standing all alone in the rain, while the rest of the gang had retreated into the barracks and were watching me through the window, smirking.

Four French workers are assigned to my base to remove the waist-high stone walls bordering the fields and pastures to create a better field of fire. They do it reluctantly and work very slowly. I can sympathise with them. Today only three have come and I ask about the missing one. I also tell them that I would have noticed their sluggish work and also know their motives. They admit it. They had been in the navy and had taken part in the scuttling of the French fleet at Toulon, so as not to let it fall into German hands. They mourn the loss of their proud ships, declare the sinking to be nonsensical and are generally very depressed about the military collapse of their fatherland. What exemplary national consciousness!

This damned barbed wire! During my inspection rounds I inevitably have to pass through several of these barriers and tear my coat every time. Tonight I tore another finger-length triangle.

During a walk through Le Conquet, I meet a girl who smiles at me in such a friendly way that I feel almost obliged to approach her. But it remains just a conversation. She is engaged and not available for walks. But maybe the engagement was just a protective assertion against too quick approval. Perhaps I should have pleaded a little longer?

Our battalion is relieved and transferred to Saint-Renan.[6] I’m taking over the heavy mortar platoon again. My teams are billeted in the small hall of an inn and I am given quarters originally intended for the company commander. The owner of the flat, Mme.[7] Jacob, tells me that she is indescribably happy about this change. The boss had been a bit scary for her. I can well imagine that. Captain Degener, with his broad, massive peasant figure and fleshy bulldog face, must have seemed to the Frenchwoman like the feared German “Hun” in the flesh. But Degener is basically a good-natured fellow, although he can put the screws to people he doesn’t like. He is a farmer - almost all machine gun company commanders are farmers - and a former twelve-rounder. He hopes for promotion to major, but the battalion commander won’t let him come up, just like he did me back then. And the distinguished, cultured, arrogant regimental commander doesn’t like the peasant anyway. Degener senses the trouble he is being made to go through. Once when I sat with him in the evening in his quarters, he complained bitterly about the cabals of his superiors. He seems to have a soft spot for me, because he often asks me about this and that and also calls on me whenever he needs support. Only yesterday I interpreted at his negotiation with a miller about a flour delivery for the company. He has often asked me for my opinion on matters. And since on top of all that I can ride well, he is obviously very pleased with me. The critical and suspicious superior in Majaki (“... let’s see what kind of sheik you are...”)[8] has almost become a trusting comrade.

According to all accounts, he later became the leader of a Turk battalion.[9] So although he was promoted, he was to a certain extent shunted off.

The selection of battalion commanders was not always happy. The high officer losses enforced a less strict selection. Many sergeants and first sergeants of the old Reichswehr were promoted to officers, and many of them reached the rank of major in the course of the war. These “Zwölfender” (twelve-rounders) were long-serving, mostly efficient professional soldiers who knew their trade very well. But they often lacked the prerequisites for the more advanced tasks of a higher officer. Not so much the military qualifications as the comprehensive education, farsightedness, worldly wisdom, leadership and more. In many of them, the old sergeant-major type came through again and again.

When Captain Degener, as the longest-serving officer in the battalion, replaced the battalion commander who was on leave, he handed over the command of the company to me. He also urged me to hold the NCO riding lessons as often as possible. Later, unfortunately, I had to confess to him that I had only held NCO riding lessons and riding training twice, because I had been kept in the orderly room for hours due to the paperwork.

This morning I get an order to send six men for the formation of a new unit that is to go to Russia. At morning roll call, I read the order to the company and then, as is customary, first ask for volunteers. It’s a thankless task to pull men out of a unit they’ve settled into. Especially when they have to go to Russia. But I experience one of my greatest surprises. Several volunteers come forward, so I have to call in only one without his consent. After the roll call, I have them come into the orderly room and ask them one by one in private why on earth they want to go back voluntarily from comfortable France to murderous Russia. The answers are both astonishing and shocking.

The first one answers me:

“My brother is in Russia, and I don’t want to have it any better than he does.”

The second says:

“If my friend has to go to Russia, then I will go with him.”

The third declares:

“I like it better in Russia.” He is an East Prussian farmer, and the Russian landscape with its villages and predominantly rural character reminds him of his East Prussian homeland. For the sake of this sense of home, he even accepts hardship and danger of life.

So everyone has their valid reason, and I cannot deny these men my respect. How many valuable character traits there are in these simple people! God grant that such a spirit and such an attitude may be preserved in our people! That people for the sake of a greater cause - be it brotherly love, love of country, friendship or religion - want to give up their comfortable lives and risk their lives!

Our soldiers behave very decently - with exceptions - and at least outwardly have a thoroughly friendly relationship with the French. Unfortunately, there are always individual antisocials who endanger this good relationship. Today, the landlady of the inn where my men are staying told me the latest news hot off the press: for some time now, several bottles of liquor have been disappearing from her cellar. That’s why her brother-in-law and some French friends armed themselves with clubs and took up vigil in the cellar. They caught the thief on the very first night. It was Max’s cleaner, whom the hotel landlady in Lannion had also already suspected of theft. Max, who had just returned from holiday and had taken over the company again, wanted to give him only three days’ arrest. But then, on the battalion’s orders, proceedings were initiated against him, which ended with his demotion to private. That was absolutely right. It is hoodlums like this who damage the reputation of the Wehrmacht and the Germans. Nobody talks about the thousands of decent soldiers, but the act of a single rascal goes through the public like wildfire. The landlady has the decency to add that there are good and bad people everywhere. My men don’t cause her any inconvenience and we have a very friendly relationship. Sometimes I get butter from her, sometimes she gets her black-haired niece to do something for me. One of her maids sewed my sports shorts, and now and then we eat together in her little guest room behind the taproom. I tell her that the lance corporal had been demoted to common soldier because of another offence he had already committed. She hears this news with satisfaction.[10]

Equally friendly are my own accommodation providers, a middle-aged widow who runs a wine wholesaling business with her sister. Her husband was killed as a reserve officer in the war against us.[12] She has a son in a Paris boarding school and a 15-year-old daughter at home, in whose young-girl’s room I now live. I have rarely slept in such a comfortable bed as this double bed. In the evening after duty I am often with the hosts, who, by the way, still have their old mother with them.[13] Mme Jacob is an extremely lively and spirited lady, despite her no longer quite youthful age. With genuine womanly curiosity, she is interested in all my circumstances, food, drink, clothes and is not at all afraid to tell me very spiritedly what she does not like. She also asks about my political views and tells me that my predecessor, a young lieutenant, had been a convinced Nazi. Recently she asked me whether the officers got the same rations as the enlisted men and whether we always got the same modest cold rations in the evenings. When I answered in the affirmative, she declared that she could no longer stand by and fried me a large meatball. So she had also observed what my orderly was always bringing me. When Mme Jacob saw me for the first time wearing a peaked cap, she said very vividly that I should always wear this cap. It looked much better than the side cap. Then she told me about Polish officers who had spent some time here and were dressed with elegance. She doesn’t think much of the English, by the way, but she has a soft spot for the Americans.

Our training service here takes place on the autumnally appealing[14] pastures surrounding the city. These pastures are surrounded by overgrown stone walls, like the Knicks in Schleswig-Holstein or the Wallhecken of Westphalia. One day, Mme Jacob observes our return from field duty and the dismissal of my company. When I return to the flat, she tells me that she was surprised at the sharpness of my voice. She didn’t expect me to have such a commanding voice. Not exactly a compliment. Another time, she met one of our companies on the street, just back from field duty, marching through the streets singing. There was one verse sung, one whistled and one hummed. She had never heard anything like it and was quite delighted.

One evening, Mme Jacob introduces me to a teacher with whom the three of us sit together. The teacher is filled with the idea of Franco-German cooperation and advocates it so eloquently that I can hardly get a word in edgewise. Of course I understood everything he said, but before I had formulated an answer, the teacher had already moved on. Then, when he had gone, Mme Jacob told me not to hold it against her, but “vous avez été d’un calme désarmant”. You were of a disarming calm. A few days later I meet the teacher on the bus. I greet him, but he deliberately overlooks me.

In my men’s quarters, I sometimes meet a girl. She is a photographer and has the soldiers give her photos, which she enlarges and colours. She tells me about her work and asks if I also have something for her to do. I didn’t have any photos that were worth processing. But you don’t always have to do business with each other. We both agree on that. Once she is in my room, my cleaner is bringing me the cold rations. Mrs. Jacob sees that I have a visitor. She doesn’t like that at all, and when I go over to her in the evening, she gives me a spirited telling-off. So I met up with the girl another time in Sergeant NN’s quarters, and as the comrade leaves the room, I suddenly hear an excited woman’s voice hissing behind the door to the next room: “Ils sont seuls maintenant!” Now they are alone! Out of spite, I cover the keyhole with my tunic, but I’m not sure if the door doesn’t have other peepholes.

Of course, we never miss an opportunity to get to Brest. We always find a reason. By “we” I mean the officers of our battalion, who, sometimes in twos, threes or fours, set off on little ventures. Once, the navy invited us and put together a small programme of visits. First we visit the large submarine bunker. It is a huge square concrete block with a 4-metre-thick concrete ceiling. Even an air mine that had smashed into it during an attack had only made a shallow dent. The interior is divided into six large boxes, each of which can hold two or, if necessary, three submarines. The entrances are closed by heavy armoured sliding gates.

Now we wait for a submarine that has just reported back from enemy action. It appears in front of the entrance and slowly glides into the bunker. While a band plays the Engellandlied, the boat moors. Then the crew disembarks. A sailor stands at the gangway and hands each crew member a large bar of chocolate. The last to come off the boat is a Tommy, whom they have fished out of the water somewhere. He doesn’t get any chocolate. We accompany the crew into the large common room of the barracks, which has already been prepared for a small reception party, and let them tell us about their lives and experiences. But they are not very talkative. They probably need rest and sleep now.

We spend the evening as guests of the naval officers in the “House of the Sea Commander”. We sit comfortably in the bar on the first floor of the house, are flattered by the navy telling us how happy they are that a battle-hardened division is securing their space and admire the two pretty French bar girls for our part.

|

Editorial 1938 1939 1940 1941 1942 1943 1944 1945 1946 1947 1948 1949 Epilog Anhang |

|

January February March April May June July August September October November December Eine Art Bilanz Gedankensplitter und Betrachtungen Personen Orte Abkürzungen Stichwort-Index Organigramme Literatur Galerie:Fotos,Karten,Dokumente |

|

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. Erfahrungen i.d.Gefangenschaft Bemerkungen z.russ.Mentalität Träume i.d.Gefangenschaft Personen-Index Namen,Anschriften Personal I.R.477 1940–44 Übersichtskarte (Orte,Wege) Orts-Index Vormarsch-Weg Codenamen der Operationen im Sommer 1942 Mil.Rangordnung 257.Inf.Div. MG-Komp.eines Inf.Batl. Kgf.-Lagerorganisation Kriegstagebücher Allgemeines Zu einzelnen Zeitabschnitten Linkliste Rotkreuzkarte Originalmanuskript Briefe von Kompanie-Angehörigen |

- ↑ Bundesarchiv, Bestand RH 26-257-27

- ↑ Not found as a real topographical designation; it is probably a military terrain baptism. Documents about it cannot be found.

- ↑ Perhaps it was also the inspection by the commander of the 7th Army from 16, 18 or 19 (not possible to read exactly) to 20 Feb 1943 or by Colonel von Anmuth, Special Staff A at Army General Office (probably on the 20th) or both (KTB 7th A Frame 000320/323).

- ↑ presumably “Lieutenant Schrödter reports with new rank!”

- ↑ the author’s then place of residence

- ↑ rather not the relocation of the division into the hinterland as mentioned in KTB OKW 1943 p. 241, 220 and 1422 and in Benary p. 112 (early April for a few days)

- ↑ Madame, Mrs

- ↑ cf. 4.4.42

- ↑ Two Turk battalions had been assigned to the XXV A.K. - for deployment with other divisions - since February; their German cadre personnel was to be reinforced as much as possible (KTB 7. A. Frame 000953).

- ↑ The story of this offence itself is not told.

- ↑ with kind permission of Bénédicte Bulle

- ↑ He died on 18 December 1939; he would have to have been fighting in Poland, or the author got it wrong.

- ↑ The relatives of Mme Marie-Louise Jacob née Le Gall (1902-1970) referred to were sister NN, husband Antoine Jacob (1897-1939), son Henri (1929-2015), daughter Jeannette and mother Marie Anne née Lan(n)uzel (1876–1958) (kind communication from Henri’s daughter, Mme Bénédicte Bulle, 2022); where was the other daughter, Annick? The wine trade had been founded in 1923 and belonged to the family until 2022, see the press articles of 2 Jan 2018 and of 26 Mar 2022 and a photo.

- ↑ in the original erroneously only autumnal; there are indeed weather conditions even at the end of winter that are reminiscent of autumn

- ↑ with kind permission of the page owner