29. Januar 1942

| GEO & MIL INFO | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OKW situation map Feb 42 | ||||

| Div leader 257th I.D. periodically: Oberst Püchler, Cdr I.R.228[1] | ||||

| 17.A. | A.Gr. von Kleist (1st Pz.A.) | |||

| 1.2.: ChdGenSt Müller GenMaj | OB: GenOb von KleistWP | |||

So the next morning[2] I set off again with the same people. This shuttle patrol is to run regularly in the future, after all, and I want to brief the people properly. Our clothes were halfway dry again overnight. (When I tried to take off my stockings last night, they were frozen to my boots). Today I'm even wearing camouflage clothing. The battalion doctor kindly offered me his white doctor's coat, which I now wear as a camouflage coat.

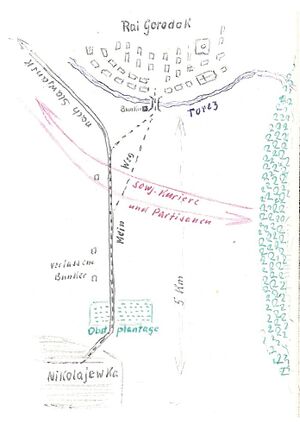

We have already crossed the orchard near Nikolayevka and are in the open plain on the “road” to Rai Gorodok. It is cold. The sky is steel blue and the air crystal clear. We can see for miles. Suddenly, three Soviet fighter planes roared in. The planes are flying low along the road. I “freeze” on the spot and the soldiers duck behind a telegraph pole. In a matter of seconds, they zoomed over us. They didn't notice us. That's almost incomprehensible, but you know how difficult it is to see anything on the ground at such speeds. Still, I didn't want to endanger my men in case the fighters came back again. I climbed into one of the empty bunkers along the road, which I knew from an earlier investigation still had a telephone connection, and called the aide-de-camps of my battalion in Rai Gorodok. I was almost invisible in my white coat, but the men were clearly visible in their green coats on the white snow. The aide-de-camps began to rage, indirectly accusing me of cowardice and not wanting to hear my proposal. So I marched off again and reached the village unmolested. At the greeting, the adjutant was cat-friendly again. Not another word was said about the matter.

This aide-de-camps was also an active twelve-rounder. In Jasło, the ambitious comrade was still a master sergeant. We met there every day for lunch in the mess hall. He never liked me.

I now go to see the company chief of the company that had fired so wildly at me the previous night. To my astonishment, it was the Upper Silesian, my old billet mate from Męcinka. At that time he was still a master sergeant. He too is a former twelve-rounder, has since been promoted to lieutenant and now leads a rifle company. He wanted to laugh himself to death when he heard that his whole company had shot at me.

From him I now learned the following about the recent attack[3]: An entire Soviet battalion had stalked across the kilometre-wide plain towards the village under cover of the nightly snow drive (that was typical Russian again!). Five hundred Red Army soldiers approached the unknowingly sleeping village. A part of them crawled, man after man, with the greatest effort in a snow-filled trench about half a metre deep, which emptied into the Torez near the bridge and the bunker. Under the protection of the Russian artillery and mortar fire, which now suddenly began, this group, protected by the embankment, ran to the bunker, attacked the unsuspecting crew from behind and slaughtered them. At the same time, the mass of the battalion rushes across the ice of the frozen Torez and penetrates the first row of houses. But that was as far as they got. The Germans had only jumped across the road into the houses on the other side of the street and had taken hold there. In the meantime it had become light. As soon as an Ivan showed himself at the window or even tried to jump across the street, he was hit and collapsed. The worst off were those who were still lying in the snow in front of the village, as if on a platter. Our soldiers shot at these targets from all houses and angles. One by one, they flinched and breathed their souls into the icy air. Even the embankment no longer offered any protection since our mortars (my platoon!) slammed their shells onto the ice. After the heaviest bloody losses, the remnants of the Soviet battalion retreated, only much faster than they had come.

This Soviet attack has again shown three remarkable facts:

1.) The Russian often attacks in the worst weather, because then he is neither expected by us, nor - in driving snow - detected in time.

2.) The Russian can endure incredibly high physical stress. This healthy people possesses a physical and mental suffering capacity that enables them to endure such heavy burdens (even if sometimes not without loud complaints).

3.) He recognises and exploits even the most inconspicuous terrain advantage. An instinct that we often already lack.

4.) The German guards are too careless and inattentive.

I take a look at the battlefield. After the battle, the Ivans who had fallen in the village had been gathered together and piled up on the village street. I am standing in front of a mountain of 95 dead and stone-hard frozen Russians. At least as many are still lying outside the village on the plain, where they can be recognised as dark dots. The snowed-in ones will not be found again until spring. It has not yet been possible to recover all the dead. Some of the people piled up on the village street were already missing pieces of clothing. The villagers had taken what was still usable.Above all, they were after felt boots[4]. They had pulled them off the feet of the dead, sometimes breaking off the frozen glass-brittle feet and leaving them stuck in the boot. The sight of this mountain of dead opponents leaves me completely cold. Only the thought of the poor mothers of the fallen fills me with quiet compassion.

The mishap with my patrol still had some after-effects, which I only learned about later, to my indignation. The blame for this mishap lay with my battalion, or more precisely with the aforementioned aide-de-camp. He

1.) neither informed me nor the neighbouring battalion of the attack on Rai Gorodok, so that when I arrived in front of the village I found a situation completely unknown to me.

2.) he did not inform the front line at the entrance to Rai Gorodok of my coming at all. It is a basic rule that the front line must be informed exactly when and where an own patrol is in the area and when and at which point it will return. So since the posts were clueless, they had to think I was an enemy. Since the posts were also still a bit nervous as a result of the Russian attack a few days ago, they had fired a bit hastily. The post even admitted that. When I told him that I had called him, he replied that he had mistaken me for a German-speaking Russian and that he had fired because I had not answered his call. But I couldn't, because I couldn't hear the call in the howling storm I had at my back, while he well understood my call, which went with the wind.

The whole affair is therefore mainly the fault of the aide, who committed two serious sins of omission. Then there was the nervousness of the post and finally the stormy weather. But the aide, in order to cover up his mistakes, turned the tables on me and accused me of clumsy behaviour. When later, after a conversation with the regimental commander about the aide's report, the connections became clear to me, it was too late. The devil takes the hindmost. That has always been the case. But the regimental commander behaved very nobly.

All my life, until today, I have always been far too modest, harmless and at times downright naïve. I have never pushed myself for promotions. I respected the "authorities" and trusted in their efficiency, justice and decency. And it was only much later, during my imprisonment and after the war, that I found out about all the intrigues and graft that went on behind the scenes.

27-29 Jan 42. For three days it has been snowing non-stop.[5] Now a gale-force wind is also setting in. The snow is already a metre high. In the morning the front doors are already so blown in that they can only be opened with difficulty.

|

Editorial 1938 1939 1940 1941 1942 1943 1944 1945 1946 1947 1948 1949 Epilog Anhang |

|

January February March April May June July August September October November December Eine Art Bilanz Gedankensplitter und Betrachtungen Personen Orte Abkürzungen Stichwort-Index Organigramme Literatur Galerie:Fotos,Karten,Dokumente |

|

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. Erfahrungen i.d.Gefangenschaft Bemerkungen z.russ.Mentalität Träume i.d.Gefangenschaft Personen-Index Namen,Anschriften Personal I.R.477 1940–44 Übersichtskarte (Orte,Wege) Orts-Index Vormarsch-Weg Codenamen der Operationen im Sommer 1942 Mil.Rangordnung 257.Inf.Div. MG-Komp.eines Inf.Batl. Kgf.-Lagerorganisation Kriegstagebücher Allgemeines Zu einzelnen Zeitabschnitten Linkliste Rotkreuzkarte Originalmanuskript Briefe von Kompanie-Angehörigen |

- ↑ KTB 257. I.D., NARA T-315 Roll 1805 Frame 000137. I.R.228 was subordinated to 257th I.D. from Jan 42.

- ↑ From the sequence of events and weather on 29, however, no flying on 29, only on 30 Jan 42 (KTB 257th I.D., NARA T-315 Roll 1805 Frame 0000104/111)

- ↑ on 27.01.1942 (KTB 257th I.D., NARA T-315 Roll 1805 Frame 000062/124), the first day of the snow drive (Roll 1804 Frame 000774)

- ↑ Surely the usual wálinki, sole-less felt boots (the author noted this term on an accompanying note)

- ↑ From 27 Jan-10 Feb 42 there was driving snow almost every day, on 28 Jan also storms, from 4-6 Feb strong easterly winds with temperatures as low as -20 °C. On 11 Feb the temperature rose abruptly to +3 °C (KTB 257. I.D. Frame 000774-000792).