4. April 1942

| GEO & MIL INFO | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Majaki | ||||

| as a machine gun platoon leader transferred to I Bn (Bn Ldr Capt Degener) and assigned to 4th Coy (Coy Ldr 2nd Lt Max Müller) Synopsis of names and positions: Regt Cdr I.R.477 Col Taeglichsbeck, Regt Ldr: Bn Cdr I Bn Maj Haarhaus, Bn Ldr: Coy Cdr 4th Coy Capt Degener, Coy Ldr: Coy Offr (and MG Plt Ldr) 2nd Lt Müller 13 Div Ldr: Oberst Püchler[1],WP | ||||

| 23 at latest de Angelis back abain | ||||

| 20th commissioned[2]: Gen d Inf von Salmuth WP | ||||

The Russians do not give up and storm us with fierce anger. A few days after we have pushed them off the plateau, they launch an attack on the village. Suddenly, a murderous fire attack pelts the village and our positions. The ground shakes and trembles. Grenades hiss through the air with a furious snort. Clanking and crashing, they slam their glowing paws into the buildings. The Russians fire with all calibres. Anti-tank shells punch large holes in the brick wall of our barn. Artillery shells smash the roof from above. Red lightning flares up as the shells burst. Already the long barn in our back is burning. I have to abandon my machine gun position and retreat with the crew through the burning barn into the next house, where we join a lurking rifle squad. The thatched roof of the barn is ablaze. Thick, black-grey smoke rolls over the ground in whirling billows, temporarily obscuring the barn. First Lieutenant Rasche appears. We stare into the billowing smoke and await the attack of the Soviet infantry. The lieutenant yells, "They’re coming!". Grey shadows flit through the clouds of smoke, appear briefly, disappear again and then come at us in a darting run. I manage to shout just in time: "They’re Germans!". It’s the light machine gun group that was securing our flank at the right corner of the barn. So we continue to wait for the Ivan, but he doesn’t come. Instead, his artillery fire races with undiminished fury over the dying village. I look around. The whole village is under fire. I distinguish the harsh barking of the anti-tank gun and the almost simultaneous tearing burst of the impact. In between, the time fuses of the flak shells crackle in the air and pelt down their hail of splinters. Somewhat less frequently, the heavy suitcases[3] of the heavy artillery buzz in, but their impacts make the earth tremble. The black-red fountains of the impacting shells leap back and forth. Dark earth shoots up like jagged crowns when the red flash of a creaking shell drives out of the earth. White lime dust or reddish dust clouds mingle in between when the shells clatter into the rubble of a farmhouse. Boards and beams whirl through the air when the barn buildings are hit. A shell hits the top edge of a brick wall and a red jet flame twitches down with the rattling stones.

Some civilians still remained behind. These farmers could not decide to leave their crofts and their village. Since their houses have been destroyed, they are living in holes in the ground. These are pits covered with boards and a thick layer of earth, where they used to store their supplies during the hot summer months. Now they crouch down here and endure the bombardment from their compatriots.

In a short pause in the firing, I jump across the road. Rifle bullets whiz around me. I don’t know if they are meant for me personally. It doesn’t matter, I’m already over there. Here lie some men from my company. They are lying flat behind a ruin of which only the foundation walls remain. Corporal Kramm is with them. He hadn’t had time to put on his steel helmet when the drumfire started. Now he’s lying there with his field cap on and an unhappy face. That surprises me, because Kramm is a good soldier. When I ask him, he answers: "Sergeant, without my steel helmet I feel as if I were naked!" Brraxx - there’s another grenade crashing into the wall. A part of it staggers and collapses, while where our soldiers press themselves against the wall, only a few bricks fall and hit the warriors in the back. They got away with the horror. I crouched ten metres away in a shell crater and was spared the impact of the stones. I had chosen this cover, remembering the old rule that shells rarely hit the same crater. But I don’t know if that’s true.

Finally the drumfire subsided. We waited in vain for the infantry attack.[4] Perhaps they were fed up after the two defeated advances or could not yet dare a new attack with their shot-up companies. They had a hard time with the Prussians.

I am leaving the rifle company. Actually, I was last assigned to the heavy machine gun platoon here, which under the leadership of Lieutenant NN was subordinated to the rifle company. I have since taken over the mortar platoon of our company again. Since not many houses are habitable any more, I am billeted together with a mortar squad in the house of our company chief. We are busily building our mortar positions[5] and are firing for adjustment into some targets and barrage rooms.

Once I have to go to the battalion command post with a mission. I descend numerous steps into the deep earth bunker. There is no end to the shaft. It’s bombproof: four layers of tree trunks! Each trunk half a metre in diametre! And above them a layer of sand several metres thick!

Since we defended Krassnoarmeisk, the Ivan has not made a single step forward. But it was also the hardest fighting and the greatest artillery fire I have experienced so far.

Gradually things quieten down around the town.[6] From time to time the red artillery fires single shots into the town, but attempts to capture it become rarer and weaker. The Soviets have not achieved their most important tactical goal, the capture of Slavyansk. They did not even succeed in completely encircling the city and cutting it off from rearward communications.It is true that we were temporarily cut off and our food rations had been severely cut, but we were always able to fight our supply routes free. Especially now that the Russian large-scale attack between Kharkov and Slavyansk has failed despite its threatening initial successes and is turning into a disastrous defeat, the pressure on Slavyansk is also easing noticeably. Now even the first leave-takers are going home. The first since the beginning of the campaign.

However, the partisans are still stirring. Again and again, individuals or whole groups are caught. Yesterday, one was caught who had been giving flashing signals with an electric torch for days. He had been observed for a short time and then arrested. Through interrogations and investigations it was established that about 700 partisans were active in the Slavyansk area, of whom 400 could be caught.

Winter is gradually coming to an end, and with it the Russian is losing one of his most powerful allies: General Winter!

The Russians were used to it, but we had not yet known it and were not prepared for it. And this year it had been particularly hard. Around the middle of winter we finally got winter clothing.[7] It was even good, but it arrived too late. In the meantime, thousands of German soldiers had been crippled by severe frostbite. Not entirely without good reason, the medal created to commemorate the "Winter Battle in the East", which many soldiers may wear with rightful pride, has been called the “Frozen Meat Medal” in derisive Landser jargon.

How the hard winter battles in and around Slavyansk, which I experienced and described here as a platoon leader in the small context of a battalion or my company, were seen in a larger context and what significance was attached to them, is shown by the excerpt of an account[8].

Winter is overcome. The snow is beginning to melt.

I'm transferred[9] to the 4th Company, pack my little bundle and report to the leader of I Battalion, Captain Degener, in Majaki. When I enter the low farmer's living room, he is sitting broadly and ponderously in the circle of his company leaders. I snap to attention and reel off my report. He looks at me half seriously, half suspiciously and only says: "Well, let's see what kind of sheik you are!" Then he assigns me to the 4th Company, whose leader, to my surprise, is Max Müller.[10] The lieutenant winks at me with a smile. I got to know Max Müller in Kombornia, where we were both still officer aspirant sergeants. In the meantime he has become a lieutenant. At that time, Captain Degener was also still a first lieutenant[11] in the same battalion. He was an active 12-point stag[12] in the Reichswehr.

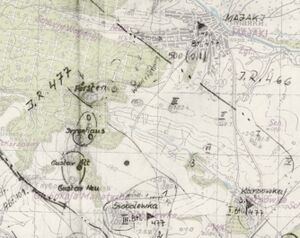

The next morning I walk the positions with Max Müller. Majaki lies on the edge of an extensive forest area, the Christishche Forest. The village is in our hands, but the forest is occupied by Russians. The last houses of the village extend into an increasingly narrow valley[13] almost like a wedge into the forest. Here is the neuralgic point of the front, a very dicey corner. That is why the last houses have been turned into strong machine gun strongpoints. From here the front runs up a bare valley slope to the right and up a wooded slope to the left. This front[14] then always runs parallel to the edge of the forest, but is always about thirty metres into the forest. The positions here also consist, as almost always, of individual foxholes or machine gun positions, often at a great distance from each other. Near the machine gun emplacements there are also earth bunkers as accommodation for the crew of four to six men.

|

Editorial 1938 1939 1940 1941 1942 1943 1944 1945 1946 1947 1948 1949 Epilog Anhang |

|

January February March April May June July August September October November December Eine Art Bilanz Gedankensplitter und Betrachtungen Personen Orte Abkürzungen Stichwort-Index Organigramme Literatur Galerie:Fotos,Karten,Dokumente |

|

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. Erfahrungen i.d.Gefangenschaft Bemerkungen z.russ.Mentalität Träume i.d.Gefangenschaft Personen-Index Namen,Anschriften Personal I.R.477 1940–44 Übersichtskarte (Orte,Wege) Orts-Index Vormarsch-Weg Codenamen der Operationen im Sommer 1942 Mil.Rangordnung 257.Inf.Div. MG-Komp.eines Inf.Batl. Kgf.-Lagerorganisation Kriegstagebücher Allgemeines Zu einzelnen Zeitabschnitten Linkliste Rotkreuzkarte Originalmanuskript Briefe von Kompanie-Angehörigen |

- ↑ nicknamed “Knödelhuber” meaning a ponderous Bavarian; Benary p. 96; was cdr I.R. 228 before, which in January 1942 became subordinated to 257th I.D.

- ↑ commencing 25 Apr (document collection IR 466 at TsAMO)

- ↑ soldiers’ language for “shell”

- ↑ In April there was daily harassing fire without infantry combat activity, on 4 April 1942 a particularly strong fire assault (KTB 257. I.D., NARA T-315 Roll 1805 Frame 000731).

- ↑ Position building is specifically mentioned on 3 Apr (KTB 257. I.D., NARA T-315 Roll 1805 Frame 000724)

- ↑ KTB 257. I.D., NARA T-315 Roll 1805 Frame 000731; from Frame 000724 onwards, the official war diary records mostly just harassing fire and, apart from reconnaissance patrols, no infantry combat activity

- ↑ The pay book p. 6/7 unfortunately only notes on 14 December 1942 “1 compl. winter set received”.

- ↑ From an account about the battles around Slawjansk (Winter Battle in the East 1941/42)

“Since the middle of January, heavy fighting has been raging here. The Soviet High Command is trying with all its might to seize Kharkov in a pincer attack. The thrust of the northern pincer arm could be intercepted near Bjelgorod and Volchansk. But the southern pincer arm, the 57th Soviet Army, had blown open the German Donets front on both sides of Izum over a width of eighty kilometres. The Soviet divisions had already struck a bridgehead a hundred kilometres deep. The tops of the attack threatened Djepropetrovsk, the supply heart of Army Group South.

Whether the Soviet incursion in the Isjum area would develop into a breach of the dam with unforeseeable consequences depended on whether the two cornerstones north and south of the breach, Balakleja and Slavyansk, could be held. Here, the battalions of two German infantry divisions had been fighting an almost legendary defensive battle for weeks. The entire development on the southern front depended on the outcome. The Berlin 257th Infantry Division held Slavyansk, the 44th Infantry Division from Vienna held the cornerstone Balakleja.

In bloody battles, the Berlin regiments under General Sachs, later under Colonel Püchler, defended the southern edge of the Isjum Arc. The combat group of Colonel Drabbe, commander of I.R. 457, fought for the miserable villages, collective farms and homesteads with such agility, bravery and readiness to make sacrifices that even the Soviet war reports, which are otherwise very reserved in their appreciation of German achievements, are full of admiration. The village of Cherkasskaya became the bloody symbol of this struggle. In eleven days, the Drabbe group lost almost half of its thousand men here. Six hundred fighters held an all-round front of fourteen kilometres. The Soviets lost 1,100 counted dead in front of this hamlet. They finally took the village, but it had also eaten their strength, the strength of five regiments.

Before Colonel General Halder had left his quarters at the 'Wolfsschanze' on the afternoon of 28 March, he had had submitted to him the combat report of the 257th I.D. on the battle which had now lasted seventy days; for the division was to be named in the Wehrmacht report: The regiments had beaten off 180 enemy attacks. 12,500 fallen Soviets had been counted in front of the division's front. Three Soviet rifle divisions and one cavalry division had been wiped out, four rifle divisions and one armoured brigade had been severely damaged. However, their own losses also showed the harshness of the battle: 652 dead, 1,663 wounded, 1,689 frostbitten, 296 missing - a total of 4,300 men, half the total losses the division had had in ten months of the Russian war: Slavyansk!”

(Excerpt from Carell 1963 p. 387 f.; underlining by the author) - ↑ earliest on 4 April and well before 13 April

- ↑ Degener (on 25 Jan still first lieutenant (reserve), in May captain acc. to KTB 257. I.D., NARA T-315 Roll 1805 Frame 001011) was commander of the 4th (machine gun) Coy (Frame 000082), which Second Lieutenant Max Müller led as deputy, while he, as senior officer of the battalion, deputised for the commander of I Bn (Major Haarhaus) at this and other occasions until Glaser took over the battalion (presumably when Haarhaus took over the regiment).

- ↑ in the original in error (cf. Officer Establishment of Inf. Rgt. 477 of 20 May 1941). "first sergeant"

- ↑ the soldiers' language term indicated the 12 years' term of service imposed by the Versailles Treaty

- ↑ according to Heereskarte Rußland (army map of Russia) 1:100,000 M-37 111-112 the Wodjanaja-Schlucht

- ↑ „Waldstellung“ acc. to KTB 257. I.D., NARA T-315 Roll 1805 Frame 000950